Below is the next installment of my paper “Gödel’s Interbellum” (revised draft, 2023); footnotes below the fold:

I will begin my survey with the self-coup of January 6, 1929, when King Aleksandar of Yugoslavia unilaterally abrogated his country’s constitution and assumed full dictatorial powers. This self-coup provides an early and ominous interwar example of a “recursive” transfer of power in which a previous extraconstitutional act is declared to be constitutional by a future constitutional act. Also, aside from Austria, the Central European country that Kurt Gödel may have been most likely familiar with was Yugoslavia. Austria not only shared a common border with Yugoslavia, during the summer of 1933 Gödel actually visited there and vacationed in the resort town of Bled with his mother.[1]

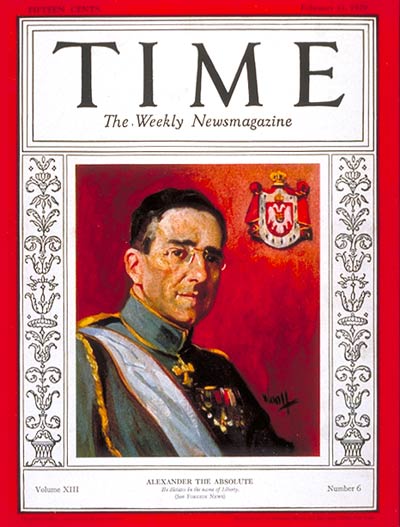

Following World War I, Yugoslavia was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and his motley kingdom consisted of a diverse and far-flung federation of crown provinces (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and the formerly independent kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro, along with an assorted collection of territories that were once part of Austria-Hungary, including Carniola, a portion of Styria, and most of Dalmatia (all from Austrian part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) as well as Croatia, Slavonia, and Vojvodina (all from the Hungarian part of the former empire).[2] Yugoslavia’s first parliamentary constitution was enacted in June of 1921 and was called the Vidovdan Constitution after the feast of St. Vitus, a Serbian Orthodox holiday that takes place every June.[3] The Vidovdan Constitution established a constitutional monarchy, led by King Aleksandar I, also known as King Aleksandar the Unifier,[4] who assumed the throne in August of 1921 and ruled Yugoslavia–first as king, then as dictator–until his assassination in October 1934.

Alas, Yugoslavia’s transition from democracy to dictatorship began as early as 20 June 1928, when the Croatian Peasant Party leader Stjepan Radić was shot by a Montenegrin Serb leader and People’s Radical Party politician Puniša Račić during a tense argument on the floor of Yugoslavia’s parliament.[5] Radić’s assassination not only embroiled Yugoslavia in political turmoil; it also allowed King Aleksandar to take full advantage of the crisis. He carried out a self-coup on 6 January 1929, proroguing the parliament,[6] abrogating the Vidovdan Constitution, and assuming full dictatorial powers.[7] Two years later, King Aleksandar formalized his dictatorship by promulgating a new constitution by decree on September 3, 1931. Yugoslavia’s new constitution, which was also known as the September Constitution or Octroic constitution, would remain in effect for another ten years, until the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers in 1941.

Did Gödel take notice of these events in neighboring Yugoslavia? Although Gödel did cross the Austro-Yugoslav border once, when he vacationed in Bled in 1933, it is unclear whether he took notice of any of these events. At the time of Aleksandar’s 6 January proclamation, for example, Gödel was in Vienna, beginning his work on his doctoral dissertation,[8] and when Aleksandar later decreed a new constitution in September of 1931, Gödel was preparing to attend a meeting of the German Mathematical Union in the spa town of Bad Elster, which is located in the state of Saxony in Germany, to give a lecture on his incompleteness theorem.[9]

Whether Gödel was aware of the September Constitution or the Yugoslavian self-coup, King Aleksandar’s decree of September 3, 1931–when he promulgated a new constitutional charter to replace the one he had abrogated in 1929–poses a deep constitutional conundrum or paradox: was this decree itself constitutional? After all, Aleksandar was acting outside his country’s constitutional process when he abrogated the Vidovdan Constitution on 6 January1929. Stated formally, Aleksandar’s abrogation of the Vidovdan Constitution effected an extraconstitutional transfer of power from parliament to king. So, from a theoretical perspective, was the 3 September decree itself an unconstitutional act, or did the decree create a new constitutional order, one that “legalized” his self-coup ex post?

[1] John W. Dawson, Jr. (1997), Logical dilemmas: the life and work of Kurt Gödel, A. K. Peters, p. 93. Bled is just across the border from the Austria in Slovenia.

[2] See, e.g., Durham, ch. 1.

[3] See, e.g., Robert J. Donia and John Van Antwerp Fine (1995), Bosnia and Hercegovina: a tradition betrayed, Columbia University Press

[4] See, e.g., Kevin Passmore (2003), Women, gender, and fascism in Europe, 1919–45, Manchester University Press, p. 104.

[5] For a history of the events leading up to Radić’s assassination, see John Paul Newman. 2017. “War veterans, fascism, and para-fascist departures in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, 1918–1941,” Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies, 6: 42–74.

[6] As an aside, the last European monarch to prorogue a parliament (i.e. suspend parliament without dissolving it) was King James II in 1685.

[7] See generally Malbone W. Graham. 1929. “The ‘dictatorship’ in Yugoslavia,” American Political Science Review, 23(2): 449–459, especially pp. 455-456.

[8] Dawson, op cit., p. 53.

[9] See Ibid., p. 75, n.12. Gödel’s lecture was delivered on the afternoon of September 15, 1931. Ibid.