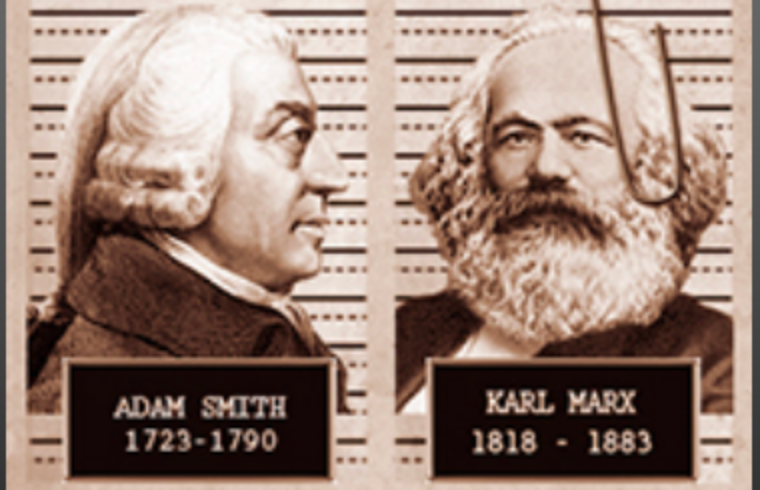

Adam Smith is often referred to as “the father of economics.” Although my colleague and friend (and co-author) Salim Rashid has questioned whether Smith is deserving of this title, [1] one thing I can say for certain is this: Smith presents a nascent theory of development economics in Book II of his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations. Why, for example, are some nations poor, while others are opulent? Book II, which is titled “Of the Nature, Accumulation, and Employment of Stock”, contains five short but crucial chapters, all of which are devoted to this key question. Smith begins by defining the concept of “stock” or capital assets in Chapter 1 of Book II. [2] For Smith, capital can be used in one of two ways:

“First, [capital] may be employed in raising, manufacturing, or purchasing goods, and selling them again with a profit. The capital employed in this manner yields no revenue or profit to its employer, while it either remains in his possession, or continues in the same shape. The goods of the merchant yield him no revenue or profit till he sells them for money, and the money yields him as little till it is again exchanged for goods. His capital is continually going from him in one shape, and returning to him in another, and it is only by means of such circulation, or successive exchanges, that it can yield him any profit. Such capitals, therefore, may very properly be called circulating capitals.

“Secondly, it may be employed in the improvement of land, in the purchase of useful machines and instruments of trade, or in suchlike things as yield a revenue or profit without changing masters, or circulating any further. Such capitals, therefore, may very properly be called fixed capitals.” (WN, II.i.4-5)

Adam Smith thus compares and contrasts fixed capital, e.g. long-term assets like buildings, tools and machines, and people(!) [3], with circulating capital, e.g. short-term assets like raw materials, inventory, and wages. More importantly, Smith’s distinction is not only relevant today — modern accounting concepts like fixed assets (“Property, Plant, and Equipment” or PP&E) and working capital (Current Assets minus Current Liabilities) can be traced back to Smith — it also goes to the core of his most enduring and original idea, the seed of which he already planted in his lengthy “Digression on the Value of Silver” in Book I of The Wealth of Nations: wealth is not about money; wealth is about economic growth via the production and consumption of goods and services, [4] or in the immortal words of Smith himself:

“To maintain and augment the stock which may be reserved for immediate consumption is the sole end and purpose both of the fixed and circulating capitals. It is this stock which feeds, clothes, and lodges the people. Their riches or poverty depends upon the abundant or sparing supplies which those two capitals can afford to the stock reserved for immediate consumption.” (WN, II.i.26)

In other words, a poor or developing nation does not make progress by accumulating or hoarding money and other assets; a nation becomes wealthy when her capital assets are put to productive use. (To be continued …)

[1] See generally Salim Rashid, The Myth of Adam Smith, Edward Elgar 1998.

[2] When Smith uses the word “stock”, he isn’t referring to securities or shares in a company (like today’s meaning of “stock”); instead, he has a broader meaning in mind: “stock” refers to capital or all the accumulated wealth or resources of a nation, including such assets as raw materials, provisions, machinery, and money.

[3] Later in this same chapter, Smith includes “human capital” in his definition of fixed capital, thus creating a whole new branch of economics. Referring to “the acquired and useful abilities of all the inhabitants or member of the society,” Smith observes: “The acquisition of such talents, by the maintenance of the acquirer during his education, study, or apprenticeship, always costs a real expense, which is a capital fixed and realized, as it were, in his person. Those talents, as they make a part of his fortune, so do they likewise of that of the society to which he belongs.” (WN, II.i.17)

[4] Cf. WN, IV.viii.49: “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production.”