I introduced Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein’s new essay “Why I am a liberal” in my previous post (see here), where I subjected the first of Sunstein’s 34 claims to critical scrutiny. To recap, I not only showed how the six ideal liberal meta-values set forth in Claim #1 (freedom, democracy, pluralism, etc.) are too broad and open-ended to be of any practical use; I also showed how these values are often in conflict with each other. Here, I will put Professor Sunstein’s second claim under my microscope. As it happens, this second claim is where Sunstein defines what he means by “liberalism” and is thus the linchpin of his entire essay.

For Sunstein, liberalism “consists of a set of commitments in political theory and political philosophy, with concrete implications for politics and law”, and most of the remainder of his essay in defense of liberalism is devoted to spelling out what these commitments and implications are. According to Prof Sunstein, liberals are for “personal agency” (Claim #4), “individual dignity” (ditto), “the rule of law” (Claim #6), freedom of speech (Claim #10), the right to vote (Claim #11), freedom of conscience (ditto), freedom of religion (Claim #12), free markets (Claim #15), and the right to property (Claim #16), and at the same time, they are against tribalism (Claim #5), public and private violence (Claim #7), and censorship (Claim #11).

By my count, then, liberals like Sunstein are “for” nine specific freedoms or rights (above and beyond the six open-ended values set forth in Claim #1), and they are against “three” other things. Having now identified what liberals are supposed to be “for” and “against”, let’s take a closer look at Sunstein’s “anti-” column, starting with his critique of tribalism (Claim #5), which I quote in full below:

5. Though liberals are able to take their own side in a quarrel, they do not like tribalism. They tend to think that tribalism is an obstacle to mutual respect and even to productive interactions. They are uncomfortable with discussions that start “I am an X and you are a Y,” and proceed accordingly. Skeptical of “identity politics,” liberals insist that each of us has many different identities, and that it is usually best to focus on the merits of issues, not on one or another “identity.”

Cass Sunstein, Why I am a [faux] liberal (Nov. 20, 2023)

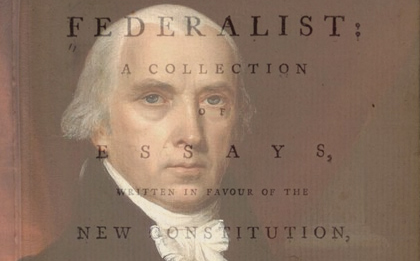

Professor Sunstein’s critique of tribalism may sound reasonable, but in reality it disguises a deep anti-liberal undercurrent, for the existence of tribes — or “factions”, to use the classical term — is an unavoidable by-product of living in a free society, or in the immortal words of a true liberal, the great James Madison:

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. *** There are … two methods of removing the causes of faction: the one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it was worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

James Madison, Federalist #10 (Nov. 22, 1787)

In other words, tribes and factions are not something to be eradicated or decried; they are to be celebrated, for factions are a sign that you are living in a free society. As a result, one’s view towards tribes and factions can serve as a liberal litmus test of sorts. If you are a faux liberal, like Sunstein, you will deplore tribes and the diversity of tribal opinions, but if you are a true liberal, you will not only tolerate tribes and factions; you will allow them to flourish!

As it happens, Federalist #10 was first published in a newspaper (The Daily Advertiser) on 22 November 1786, almost 236 years to the day that Professor Sunstein’s essay “Why I am a liberal” was published in the New York Times (20 November 2023), but truth be told, you will learn much more about the subtle paradoxes of pluralism and self-government from reading Madison than from Sunstein. (For his part, Sunstein himself should know better, since “pluralism” is one of his six liberal meta-values, although as I have showed in this blog post, pluralism does no actual work in his essay.)

Postscript: Again, I hate to be “that guy”, but my next post will expose a huge blind spot in Sunstein’s discussion of John Stuart Mill and expose the utter hypocrisy of Sunstein’s defense of “anti-caste principles”.

Pingback: The hypocrisy of Cass Sunstein (part 3) | prior probability

Pingback: Reflections on Sunstein’s liberalism and Howard’s everyday freedom | prior probability