Note: this is part 6 of my review of Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1754)

In my previous post (“Rousseau through the eyes of Adam Smith“), I mentioned how Adam Smith’s 1756 Letter-Essay to the Edinburgh Review singles out several important sections from the second part of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality — specifically, the passages corresponding to paragraphs #21, #30, #31, and #63 of the G. D. H. Cole translation, to be more exact — and I included Smith’s own translations of these three pivotal passages (see here) for good measure. Here, I will conjecture why Smith chose to include those three passages in particular in his 1756 Letter.

First off, Excerpt #1 (Paragraph #21) pinpoints the exact moment in time when “equality [among men] disappeared”. According to Smith’s translation of Rousseau, inequality emerged as soon as men in the state of nature began to cooperate with each other: “from the instant in which one man had occasion for the assistance of another, from the moment that he perceived that it could be advantageous to a single person to have provisions for two, equality disappeared, property was introduced, labour became necessary, and the vast forests of nature were changed into agreeable plains …” (Smith 1756, Para. 13).

For its part, Excerpt #2 (Paragraphs #30 & #31) not only paints a zero-sum picture of trade and commercial society (Rousseau condemns man’s “concealed desire of making profit at the expense of some other person”); this passage also purports to show a direct connection or deep link between commercial society and moral corruption. How do markets morally corrupt men? According to Rousseau, society, markets, and cooperation corrupt men in two ways. To begin with, when men are engaged in trade, each man is constantly comparing his lot in life to that of his fellow men, and furthermore, each man’s “insatiable ambition” and “secret jealousy” will cause him to lie, cheat, and steal in order to outshine his peers: “an insatiable ambition, an ardor to raise his relative fortune, not so much from real necessity, [but from a desire] to set himself above others, inspire all men with a direful propensity to hurt one another; with a secret jealousy, so much the more dangerous, as to strike its blow more surely, it often assumes the mask of good will …” (Smith 1756, Para. 14).

Lastly, Excerpt #3 (Paragraph #63) compares and contrasts man in the state of nature with modern man, man in the state of civilized society: “The savage breathes nothing but liberty and repose; he desires only to live and be at leisure …. The citizen [civilised man], on the contrary, toils, bestirs and torments himself without end, to obtain employments which are still more laborious: he labours on till his death [and] even hastens it …” (Smith 1756, Para. 15).

So, what did Adam Smith make of these passages? We know that Smith found Rousseau’s work to be highly original — see Paragraph 10 of his 1756 Letter-Essay to the Edinburgh Review — but at the same time, Smith appears to be dismissive of the substance of Rousseau’s Second Discourse. Toward the end of Paragraph 12 of his 1756 Letter-Essay, for example, Smith writes (emphasis added):

[Rousseau’s] work is divided into two parts: in the first, he describes the solitary state of mankind; in the second, the first beginnings and gradual progress of society. It would be to no purpose to give an analysis of either; for none could give any just idea of a work which consists almost entirely of rhetoric and description.

Although Smith says that “it would be to no purpose to give an analysis” (see the full quotation above) of Rousseau’s Second Discourse, one of the ironies of Smith’s 1756 Letter-Essay is that he (Smith) does just that in Paragraphs 11 and 12 of his letter. Among other things, Smith points out two problems with Rousseau’s work. One is Rousseau’s incomplete picture of man in the state of nature, or in Smith’s own words, “Mr. Rousseau, intending to paint the savage life as the happiest of any, presents only the indolent side of it to view, which he exhibits indeed with the most beautiful and agreeable colours, in a style, which, tho’ laboured and studiously elegant, is every where sufficiently nervous, and sometimes even sublime and pathetic” (Smith 1756, Para. 12).

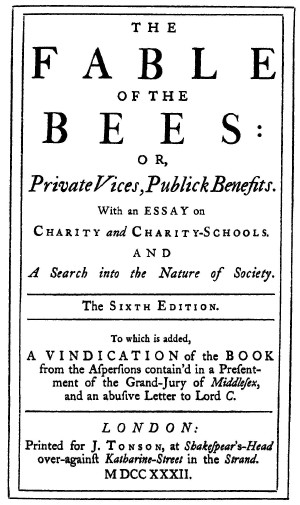

The bigger problem for Smith, however, appears to be Rousseau’s take on Bernard Mandeville, the scandalous author of The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits (see here), who famously claimed that “private vices” like self-interest produce great “publick benefits” such as wealth and prosperity. Although Smith commends Rousseau for “soften[ing], improv[ing], and … strip[ping] [Mandeville’s fable] of all that tendency to corruption and licentiousness which has disgraced them in their original author” (Smith 1756, Para. 11), at the same time Smith criticizes Rousseau for taking man’s innate sense of “compassion” or “pity” — which, according to Smith’s reading of Mandeville, is “the only amiable principle [that Mandeville] allows to be natural to man — “a little too far”: “It is by the help of [Rousseau’s rhetorical] style, together with a little philosophical chemistry, that the principles and ideas of the profligate Mandeville seem in [Rousseau] to have all the purity and sublimity of the morals of Plato, and to be only the true spirit of a republican carried a little too far” (Para. 12).

To conclude, although Adam Smith admires Rousseau’s originality and rhetoric, Smith disagrees with the substance of Rousseau’s argument. As it happens, Smith has much more to say about Mandeville and Rousseau in his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which was first published in 1759. (See here, for example.) To what extent should Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments — and The Wealth of Nations, for that matter — be read as a direct reply to the works of Rousseau and Mandeville? That is a question I will consider in a future post …

Pingback: Postscript to Rousseau’s Second Discourse | prior probability