Note: Below I review Chapter 5 (pp. 36-52) of Philip K. Howard’s Everyday Freedom: Designing the Framework for a Flourishing Society, available here (Amazon).

In a previous post, I summed up Philip K. Howard’s three-part critique of modern law, a critique that first appears in Chapter 3 of his beautiful new book Everyday Freedom: too many rules, too many procedures, and too many rights. In Chapter 5, which picks up where Chapter 3 leaves off, Mr Howard elaborates on each one of these points and makes a number of valid points:

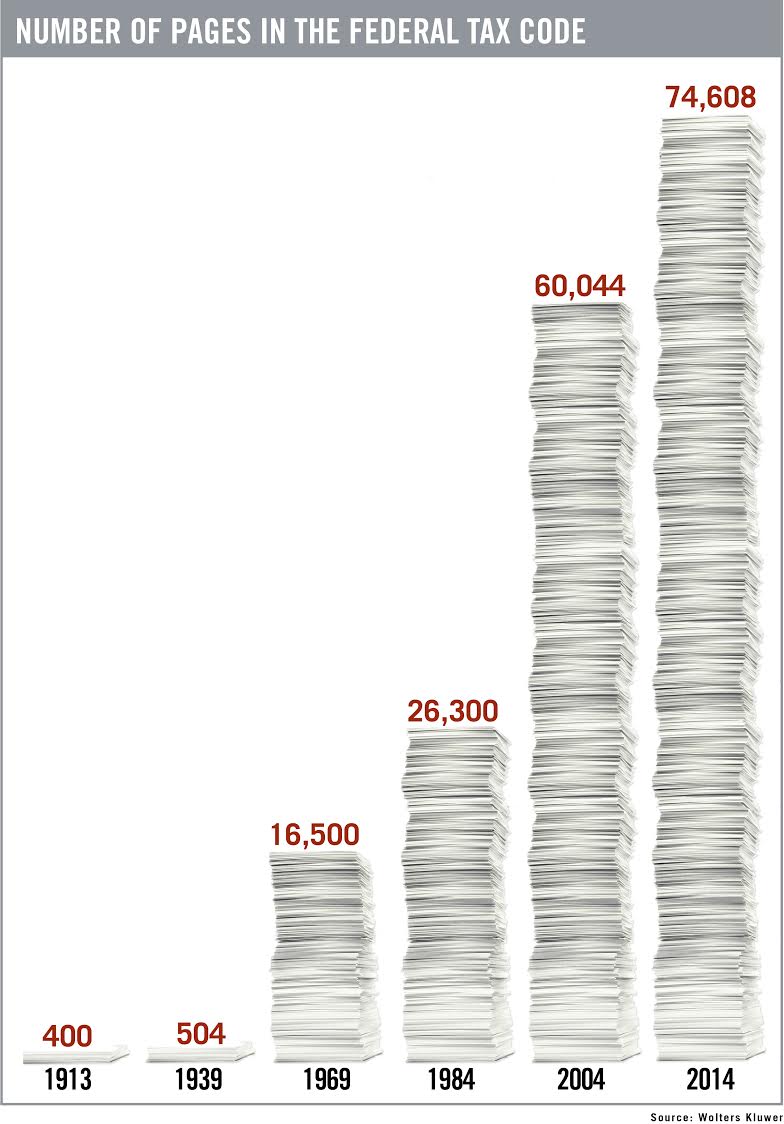

- Too many rules. Howard not only denounces the sheer volume of rules and regulations that are currently on the books — in the domain of federal regulation alone, for example, there are 150 million words of binding legal requirements (p. 39) — he also explains why legislatures and public agencies are motivated to produce so many rules in the first place: the desire for certainty or, in Howard’s own words, “the quest for clear law” (p. 37). Ironically, however, as Howard himself correctly notes, the greater the number of laws, the greater the amount of legal and regulatory uncertainty, since many of these rules are contradictory and since no one can “know” with any degree of certainty what the law is.

- Too many procedures. Additionally, Howard correctly points out just how time-consuming and expensive it is to get one’s day in court — the culprit here being Byzantine procedural rules — so expensive and so time-consuming that the right to a jury trial — our greatest constitutional right of all, I might add — is all but illusory. Again, Howard’s critique is spot on.

- Too many rights. Last but not least, Howard bemoans what one legal scholar (Jamal Greene) calls “rightsism“: the proliferation of legal rights and “protected categories” (p. 45) that began in the 1960s and continues unabated. Why is this so-called “rights revolution” such a bad thing? Because, as Howard correctly notes, rights are invoked strategically by litigious plaintiffs attorneys and so-called “public interest” groups in order to “weaponize[] law” (p. 46) in one of two ways: either to extort money payments from business firms or to bypass legislatures to get courts to impose their preferred public policy outcomes.

Although Howard’s three-part critique of modern law is on point, his proposed prescription or medicine for these ills is off the mark. Stay tuned! I will explain why — as well as conclude my review of Everyday Freedom — in my next post …

Pingback: What Howard gets wrong: review of Everyday Freedom, part 4 of 4 | prior probability

Pingback: Reflections on Sunstein’s liberalism and Howard’s everyday freedom | prior probability