As Alain Alcouffe and I have mentioned in our previous two posts (see here and here), much of the scholarly attention to Adam Smith’s sojourn in Switzerland has been devoted to Geneva’s proximity to Ferney, where Smith’s hero Voltaire lived at the time, and to their (Smith and Voltaire’s) mutual interest in the l’affaire Calas or “Calas Affair”, an unjust criminal-religious prosecution that had taken place in Toulouse, France, in 1762. But what most Smith scholars have overlooked is that the little Republic of Geneva was itself the scene of an even more famous intellectual crime that same year, for it was in 1762 that the austere Calvinist authorities in Geneva banned what would become one of the most influential works of political philosophy and issued a warrant for its author’s arrest. (See, e.g., Mason 1993, p. 568.)

Who was this would-be criminal, and what was his great intellectual crime? He was none other than a citizen of Geneva, the great Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and his crime was the publication of Du contrat social; ou, Principes du droit politique. (In addition to The Social Contract, Rousseau’s treatise on education, Émile, was also banned.) Rousseau, now an international fugitive (his works were banned in Paris too), reacted to the suppression of The Social Contract in Geneva by renouncing his Genevan citizenship in 1763 and then indicting the republican regime of that city-state in a letter-essay titled Lettres écrites de la montagne (1764), the last work of Rousseau’s to be published during his lifetime. For his part, given his review of one of Rousseau’s earlier works in his 1756 letter-essay to the Edinburgh Review, Smith must have taken an interest in these developments. (Also, for what it’s worth, a copy of Lettres écrites de la montagne made its way to Adam Smith’s private library. See Mizuta 1967, p. 53.)

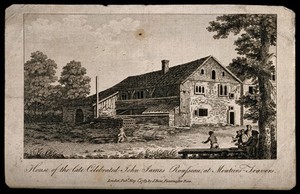

Moreover, Rousseau was still living in the vicinity of Geneva at this time. After his works were declared illegal and a warrant issued for his arrest, he relocated to Môtiers (close to Geneva but outside her legal jurisdiction) in the summer of 1762 and remained there until mid-September 1765. (See here, for example; Durant & Durant 1967, p. 51.) It was during Rousseau’s 26-month residency in Môtiers that he wrote Letters from the Mountain, drafted a constitution for Corsica, and was visited by Adam Smith’s former student, James Boswell, but Rousseau was finally forced to flee after his house (pictured below), which today is a museum, was stoned by a mob on the night of 6 September 1765. (Ibid.) Rousseau then found refuge for a few weeks in a solitary house on the Île de St.-Pierre (St. Peter’s Island) in the independent city-state of Bern (also not far from Geneva), until the Senate of Bern ordered him to leave the island and the canton within fifteen days on 17 October 1765. (Ibid.) On 29 October 1765, Rousseau left Switzerland, never to return.

Whether or not Smith was aware of Rousseau’s dramatic departure from Switzerland, both of Rousseau’s Swiss sanctuaries — the house in Môtiers and the solitary caretaker’s house on St. Peter’s Island — were located near Geneva. Given this geographic proximity, perhaps Smith had every intention of meeting with Rousseau during his sojourn in Switzerland. Among other clues, Smith’s library would eventually contain no less than 15 volumes of Rousseau’s works. (See Mizuta 1967, p. 53.) By way of comparison, although Voltaire was an even more prolific author than Rousseau, only six of Voltaire’s volumes found their way into Smith’s library. (Ibid., p. 60.) Furthermore, if the amount of space Smith devoted to Rousseau in his 1756 letter-essay to the Edinburgh Review is any indication — no less than six out of the 17 paragraphs of this work are addressed to Rousseau, compared to just one paragraph to Voltaire — we can safely say that Smith admired Rousseau as much as, if not more than, Voltaire.

Alas, Adam Smith never did get to meet Rousseau, for by the time the Scottish philosopher had arrived in Geneva, Rousseau was about to take flight from Switzerland for good. So why did Smith stay in Geneva for as long as he did, possibly until end of January or beginning of February 1766? Maybe Smith expected Rousseau to find refuge in some other canton close by or maybe even resurface in his native Republic of Geneva to answer the charges against him. (In the meantime, Smith must have discussed Rousseau’s fate and fugitive status with Voltaire when the two intellectual giants finally met in Ferney.) Either way, as my colleague Alain Alcouffe and I will explain when we resume this series next week, Adam Smith would find many more good reasons to remain in Geneva …

Pingback: Rousseau against the world | prior probability

Pingback: January 1766: prologue | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith in Switzerland | prior probability