Although Alain Alcouffe and I have already described what we call “the fracas at Ferney” or “Dillon Affair” in our previous two posts (see here and here), we shall now restate the relevant facts and main sequence of events below for reference (our footnotes appear below the fold):

(1) The setting: A hunting party consisting of five men, including one Charles Dillon, a young English aristocrat who had a reputation for gambling [see footnote 1], is trespassing somewhere on Voltaire’s private property, located a few miles northwest of Geneva in the village of Ferney, on the morning of Saturday, Dec. 7;

(2) Inciting incident: Next, one of Dillon’s hunting dogs is killed–most likely by one of Voltaire’s gamekeepers, either by accident or in self-defense (perhaps the dog had attacked the gamekeeper), or if Voltaire’s mistress Madame Denis is to be believed, the hound was killed by “the townspeople of Ferney” (“les gens du village de ferney“);

(3) Escalation of the conflict: Angry at the killing of his dog, Dillon not only threatens to burn down Voltaire’s house; he also rounds up four men armed with rifles and pistols (“quatre personnes armées de fusils et de pistolets“) and returns to Voltaire’s estate on Monday, Dec. 9, searching for the gamekeeper who he believed had killed his bloodhound and threatening to capture him “dead or alive”;

(4) Voltaire retaliates with a lawsuit: The very next day (!), Tuesday, Dec. 10, Voltaire and Madame Denis initiate legal proceedings against Charles Dillon, alleging that “[t]he gamekeeper whom Mr Dillon pursued with force in Ferney, attempting to escape from him, broke his back and is in life-threatening condition” (“Le garde chasse chez lequel Monsieur Dillon alla avec main forte à ferney, aiant voulu se dérober à sa poursuitte, s’est cassé les reins, et est en danger de la vie“);

(5) Voltaire’s mistress’s legal memo: And last but not least, Madame Denis — or perhaps it was Voltaire himself — drafts a legal memorandum dated Dec. 10-11 explaining her side of the story, a copy of which somehow ends up with Adam Smith.

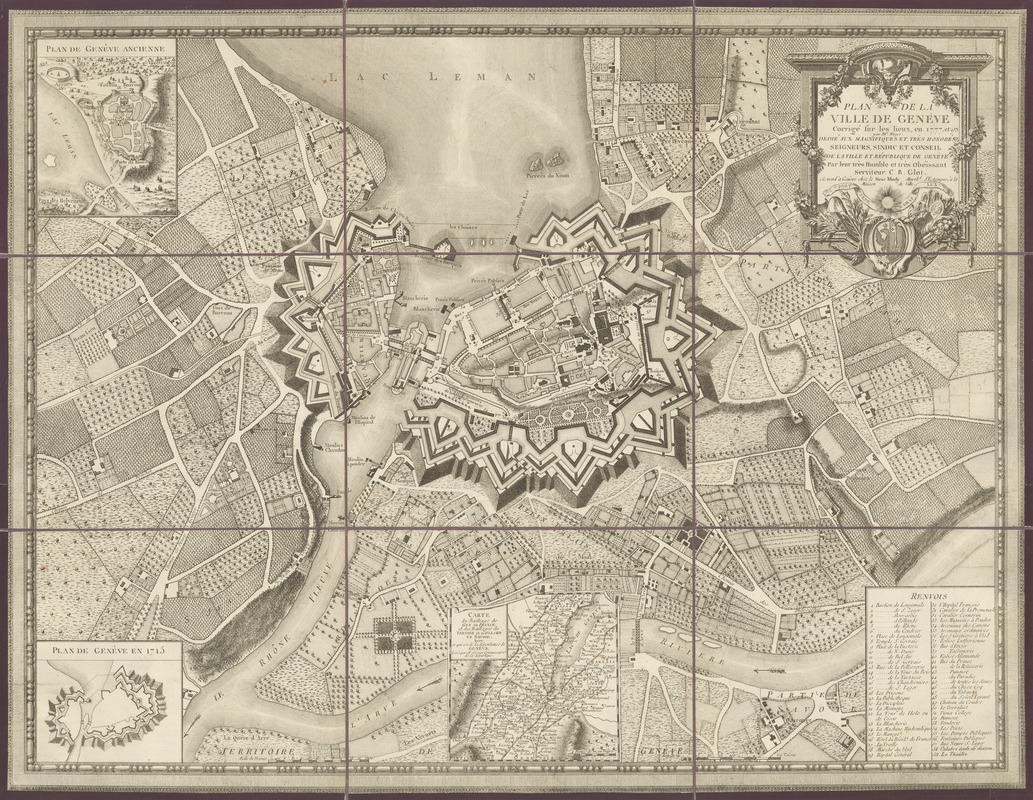

Did Charles Dillon ever answer the charges against him? What was the outcome of this peculiar case? And most importantly, what does Adam Smith have to do with any of the events described above? We know the Scottish moral philosopher and travelling tutor was residing in Geneva at the time (a map of which, circa 1777, is pictured below) and that he was most likely already personally acquainted with the great Voltaire — according to one historical account [see footnote 2], for example, Smith had visited Voltaire five or six times during this period — but what we do not know is why he received a copy of Madame Denis’s memorandum.

In brief, as far as Alain Alcouffe and I can tell, there are three possible reasons why Voltaire, via Madame Denis, might want to keep someone like Adam Smith in the loop:

One possibility is strategic: maybe Madame Denis simply wanted to share her side of the story with Smith and his pupils Duke Henry and Hew Campbell Scott — recall that Smith was still a travelling tutor during his sojourn in Switzerland — or at least put them on notice that something serious had occurred at Voltaire’s estate, especially since her complaint is directed against a young English aristocrat who might have been personally known to Smith or his pupils. (Recall that Geneva’s population was not only small (about 24,000 inhabitants); the Swiss city-state was also a popular grand tour destination for British travellers at the time [see note 3].) Another clue along these lines is that Madame Denis’s legal memorandum is not addressed to Adam Smith in particular; instead, she writes, referring to herself in the third person, that “Madame Denis submits these actions to the judgment of all the English gentlemen currently in Geneva” (“Madame Denis fait juges de ces procédés tous les gentils hommes anglais qui sont à genêve“).

Another possibility might have to do with the pending legal proceedings that Voltaire and Madame Denis had already initiated against Charles Dillon on Tuesday, Dec. 10. That is, perhaps they wanted to recruit Smith to participate in the case, either as an informal advisor or as maybe even as a witness, especially if one of Smith’s previous visits to Ferney coincided with Charles Dillon’s original hunting excursion on Saturday, Dec. 7, or with his return on Monday, Dec. 9, when Dillon rounded up four armed men and chased Voltaire’s gamekeeper. According to one historical source (Samuel Rogers, see note 2), the Scottish philosopher had met with Voltaire no less than five or six times during his sojourn in Switzerland, so it’s possible Smith might have been present at Ferney during one or more of the events described in Madame Denis’s legal memorandum and would thus be needed as a witness.

But the most intriguing possibility is this: what if either Duke Henry or Hew Campbell Scott were out hunting with Charles Dillon when the dog-killing incident took place on the 7th? By her own account, Madame Denis reports in her legal memo that no less than five men were hunting on Voltaire’s private property. She identifies two of these men by name — the wrongdoer Charles Dillon and a local carpenter, Joseph Fillon — but that leaves three unidentified hunters. It is therefore entirely possible that the remaining members of Dillon’s Saturday-morning hunting party included one or both of Adam Smith’s pupils. Moreover, given Dillon, Duke Henry, and Hew’s aristocratic pedigrees and hunting’s widespread popularity as a pastime of the British aristocracy [see note 4], this intriguing possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand.

Alas, we may never know which of the three possibilities described above is the true reason why Madame Denis’s legal memorandum ended up in Smith’s personal possession, but we do know this: at this very moment in time, the great Voltaire was also embroiled in a bitter scientific dispute with Dillon’s English tutor, John Turberville Needham, a leading contemporary natural philosopher and member of the prestigious Royal Society. Did the Dillon-Voltaire dispute have anything to do with the ongoing Needham-Voltaire Affair? Alain Alcouffe and I will entertain this possibility — as well as consider Adam Smith’s possible connection to the Needham-Voltaire controversy — in our next post …

Footnotes:

[1] See Caroline Moorehead, Dancing to the Precipice: Lucy de La Tour du Pin and the French Revolution, London: Chatto & Windus (2009), p. 41.

[2] See P. W. Clayden, The Early Life of Samuel Rogers, Boston: Roberts Bros. (1888), p. 84; see also John Rae, Life of Adam Smith, London: Macmillan (1895), p. 189.

[3] See, e.g., Mavis Coulson, Southwards to Geneva: 200 Years of English Travellers, Stroud: Sutton Publishing (1990).

[4] See, e.g., Barry Lewis, Hunting in Britain from the Ice Age to the Present, Stroud: History Press (2009).

Pingback: Adam Smith and the Voltaire-Needham Affair | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith in Geneva: arrival | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith in Switzerland | prior probability