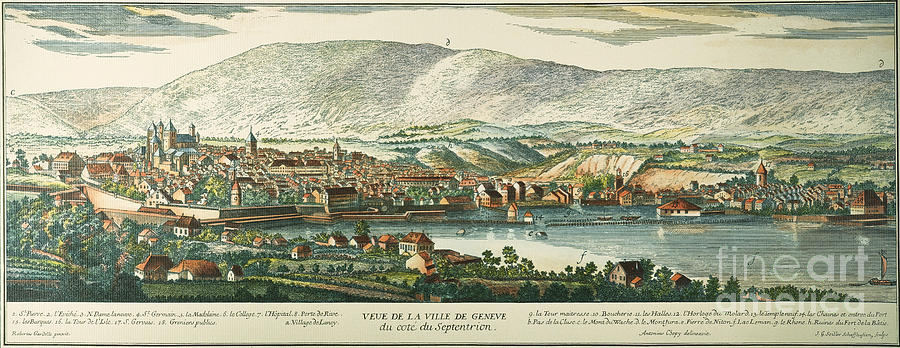

In addition to the great Voltaire and his mistress Madame Denis, Adam Smith met and befriended many other noteworthy men and women during his extended sojourn in the picturesque Swiss city-state of Geneva (pictured below, circa 1780). Among these illustrious individuals are (in alphabetical order) Charles Bonnet (1720–1793); Marie Louise Elisabeth de La Rochefoucauld, the duchesse d’Enville (1716–1797) and her son Louis Alexandre de La Rochefoucauld, 6th Duke of La Rochefoucauld (1743–1792); Georges-Louis Le Sage (1724-1803); Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl Stanhope (1714–1786), his wife Grizel Hamilton (Lady Stanhope), and their son Charles, who would become the 3rd Earl Stanhope; and last but not least, Theodore Tronchin (1709–1781). Another person, however, who should be added to this list of international luminaries in Adam Smith’s exclusive Geneva circle is “the Syndic Turretin“. [On this note, see John Rae, Life of Adam Smith (1895), p. 191.]

But who exactly was this Turretin, and what did Adam Smith learn from him? Alain Alcouffe and I will turn to those questions in our next post; in the meantime, we will say a few words about Turretin’s title or honorific, “Syndic”. One historical source identifies “Le Syndic Turretin” as the “Mayor” of Geneva [see Warwick Lister, Amico: The Life of Giovanni Battista Viotti (2009), p. 43], while for his part Smith’s biographer John Rae calls him “the President of the Republic” [Rae 1895, p. 191]. But as we shall see in our next post, Turretin was neither a president nor a mayor, properly speaking. Instead, it would be more accurate to describe him as one of four chief magistrates of the Geneva Republic, for at the time, Geneva was led by four syndics. (For reference, see this entry in d’Alembert and Diderot’s famed Encyclopédie.) This observation, in turn, is noteworthy for us because, in his capacity as syndic or magistrate, Turrentin may have been called on to resolve the legal dispute between Voltaire and Charles Dillon (the Dillon Affair), and he may have also been instrumental in his city-state’s decision to issue an arrest warrant against the great Rousseau and ban his works in 1762 … (to be continued)

Pingback: The Scottish moral philosopher and the Swiss statesman, part 2 | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith in Switzerland | prior probability