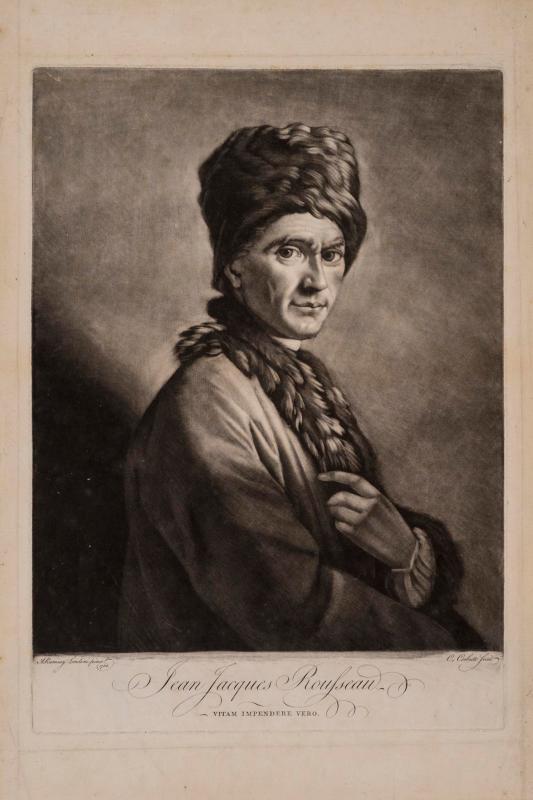

Alain Alcouffe and I have been researching Adam Smith’s sojourn in Switzerland. More specifically, we have posed a number of questions about this chapter of Smith’s life. Did he, for example, take an interest in the whereabout of Jean-Jacques Rousseau or in the suppression of his works by the syndics of Geneva, and if so, whose side was Smith on, Geneva’s or Rousseau’s, the censoring syndics’ or his fellow philosopher’s?

The answer to our first question is clear enough, for if Smith’s 1756 letter-essay to the Edinburgh Review is any indication, the Scottish moral philosopher took notice of Rousseau long before his (Smith’s) subsequent sojourn in Switzerland in late 1765/early 1766. Simply put (as Alain Alcouffe and I have previously conjectured; see here and here), it is reasonable to assume that it was Rousseau’s celebrity, if not his notoriety (especially after a warrant for his arrest was issued in his native Geneva in 1762), that motivated the Scottish philosopher’s visit to Geneva in the first place!

Furthermore, we know for certain that Smith later took a keen interest in Rousseau’s quarrel with David Hume and that he (Smith) took Hume’s side in this matter. (See, for example, Adam Smith’s 6 July 1766 letter to David Hume; Corr. #93.) Even after this great literary affair had run its course, the future economist continued to inquire about Rousseau’s whereabouts. In a letter to David Hume dated 7 June 1767 (Corr. #103), Smith asks, “What has become of Rousseau? Has he gone abroad, because he cannot continue to get himself sufficiently persecuted in Great Britain?”

Likewise, in a letter addressed to Smith from one of his grand-tour contacts in Paris–the Comte de Sarsfield (1718–1789), a French military officer of Irish ancestry–his interlocutor volunteers information about Rousseau’s whereabouts: “They say Rousseau is in St Denis.” (Corr. #109) Why would Count Sarsfield bother revealing this detail to Smith unless he thought it would be of interest to him? And in another letter from Adam Smith to David Hume–this one dated 13 Sept. 1767 (Corr. #109)–Smith writes, “I should be glad to know the true history of Rousseau before and since he left England.”

It is therefore reasonable to assume that Rousseau’s whereabouts–as well the real or imagined persecutions against him–were important topics of conversation during Smith’s sojourn in Switzerland in late 1765/early 1766, but what did Smith think of his fellow philosopher? Did Smith side with the syndics of Geneva, who censored Rousseau’s works in 1762 and issued an arrest warrant against the offending author, or did the future economist and champion of “natural liberty” defend Rousseau’s right to express his ideas, however radical those ideas might be?

Alas, neither Alain Alcouffe nor I have found any direct or contemporaneous evidence of Adam Smith’s position on Rousseau’s troubles in his native Geneva, but what should we make of Smith’s silence? On the one hand, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, especially considering that most of Smith’s private papers and correspondence were destroyed at Smith’s own request on the eve of his death in July 1790, but at the same time, the Scottish philosopher’s few subsequent references to Rousseau provide us some clues. Specifically, whatever his views of Rousseau were in the fall of 1765 (when Smith was residing in Rousseau’s hometown of Geneva for several months), Rousseau–like Voltaire–must have lost whatever luster he had prior to Smith’s sojourn in Switzerland, for just a few months later (July 1766) Smith would update his priors, so to speak, and conclude that Rousseau was a “rascal” (cf. Corr. #93). We therefore think it is safe to say that Smith, like Hume (cf. Corr. #96), saw Rousseau either as a “villain” or a “madman” (ibid.). Either way, Smith must have concluded that Rousseau’s martyr complex was the result of his own pride, vanity, and lack of self-command.

Note: Alain Alcouffe and I will resume our series on Adam Smith in Switzerland next week …

Pingback: Adam Smith in Switzerland | prior probability