Thus far, Alain Alcouffe and I have surveyed several different facets of Adam Smith’s sojourn in Switzerland in late 1765/early 1766 — such as his close contacts and encounters with the well-connected Dr Theodore Tronchin and with the great Voltaire — and we have also identified several matters of historical interest that Smith himself was either personally aware of or that might have piqued his curiosity during this chapter in his life, including the whereabouts of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the ongoing pamphlet war between John Needham and Voltaire, and the Dillon Affair (an incident that occurred on Voltaire’s country estate at Ferney in December 1765).

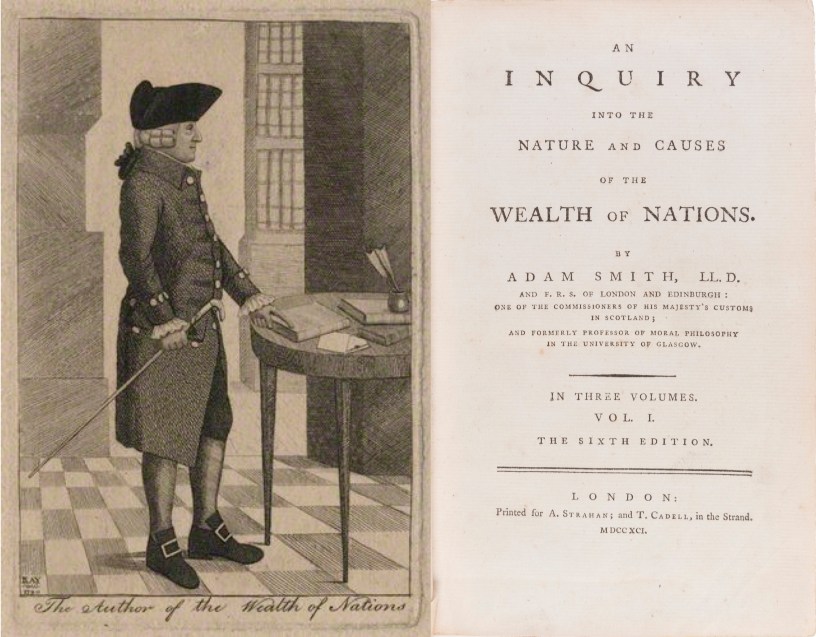

But what did Adam Smith learn during his Swiss sojourn? If the dozen or so references to Switzerland in The Wealth of Nations — as well as the several additional references to specific cantons like Berne, Geneva, Lucerne, and Unterwald — are any indication, then the Scottish philosopher must have learned a lot during his Swiss travels! For example, in Book 1, Chapter 3 of his magnum opus on “The Rise and Progress of Cities and Towns after the Fall of the Roman Empire”, Smith explains why so many cities in Italy and Switzerland became independent city-state or mini-republics:

In countries, such as Italy and Switzerland, in which, on account either of their distance from the principal seat of government, of the natural strength of the country itself, or of some other reason, the sovereign came to lose the whole of his authority, the cities generally became independent republics, and conquered all the nobility in their neighbourhood, obliging them to pull down their castles in the country and to live, like other peaceable inhabitants, in the city. This is the short history of the republic of Berne as well as of several other cities in Switzerland. [Glasgow ed., pp. 403-404 (end para. 10).]

The bulk of Smith’s references to Switzerland in The Wealth of Nations, however, occurs in Book 5 of his magnum opus on “The Revenue of the Sovereign or Commonwealth”. For starters, Smith compares and contrasts the militias of ancient Greece and Rome with those of “England, Switzerland, and … every other country of modern Europe” in Book 5, Chapter 1 as follows:

Militias have been of several different kinds. *** In the republics of ancient Greece and Rome, each citizen, as long as he remained at home, seems to have practised his exercises either separately and independently, or with such of his equals as he liked best, and not to have been attached to any particular body of troops till he was actually called upon to take the field. In other countries, the militia has not only been exercised, but regimented. In England, in Switzerland, and, I believe, in every other country of modern Europe where any imperfect military force of this kind has been established, every militiaman is, even in time of peace, attached to a particular body of troops, which performs its exercises under its own proper and permanent officers. [Glasgow ed., pp. 698-699 (para. 20).]

Later, Smith identifies another significant difference in the organization and morale of militias in ancient versus modern times: the militias of ancient Greece and Rome “required little or no attention from government to maintain them in the most perfect vigour”, while modern militias “are constantly falling into total neglect and disuse”. [WN, Glasgow ed., p. 787 (para. 60).] But at the same time, Smith also singles out Switzerland as an exception to this general rule:

The ancient institutions of Greece and Rome seem to have been much more effectual for maintaining the martial spirit of the great body of the people than the establishment of what are called the militias of modern times. They were much more simple. When they were once established they executed themselves, and it required little or no attention from government to maintain them in the most perfect vigour. Whereas to maintain, even in tolerable execution, the complex regulations of any modern militia, requires the continual and painful attention of government, without which they are constantly falling into total neglect and disuse. The influence, besides, of the ancient institutions was much more universal. By means of them the whole body of the people was completely instructed in the use of arms. Whereas it is but a very small part of them who can ever be so instructed by the regulations of any modern militia, except, perhaps, that of Switzerland. [Ibid.]

The remainder of Smith’s references to Switzerland in The Wealth of Nations, however, deal with religion — more specifically, with the effects of religion on politics, education, and the distribution of wealth. Among other things, Smith has something to say about the politics of pastoral elections and the rise of fanatical factions in the Protestant city-states of Switzerland, about the inverse relation between the wealth of churches and the wealth of their parishioners, and about the effects of established churches on morals. Alain Alcouffe and I will revisit Smith’s sundry observations on Switzerland in our next post …

Pingback: Switzerland in The Wealth of Nations, part 2 | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith in Switzerland | prior probability