Traditionally, the law addressed [the problem of harmful effects] by asking such questions as … who caused the harm [and] who acted reasonably. Coase, however, emphasized the reciprocal nature of the problem ….” [Stewart Schwab, “Coase Defends Coase: Why Lawyers Listen and Economists Do Not”, Michigan Law Review, Vol. 87 (1989), p. 1173]

As I mentioned in my previous two posts, Ronald Coase’s “cattle trespass parable” and his resulting conception of reciprocal harms have deep and troubling implications for moral philosophy and politics, for unlike Coase most (if not all) moral and political philosophers conceive of harm as flowing in just one direction, or in the eloquent words of Coase himself: “The question is commonly thought of as one in which A inflicts harm on B and what has to be decided is: how should we restrain A?” [See R. H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost”, Journal of Law & Economics, Vol. 3 (1960), at p. 2.]

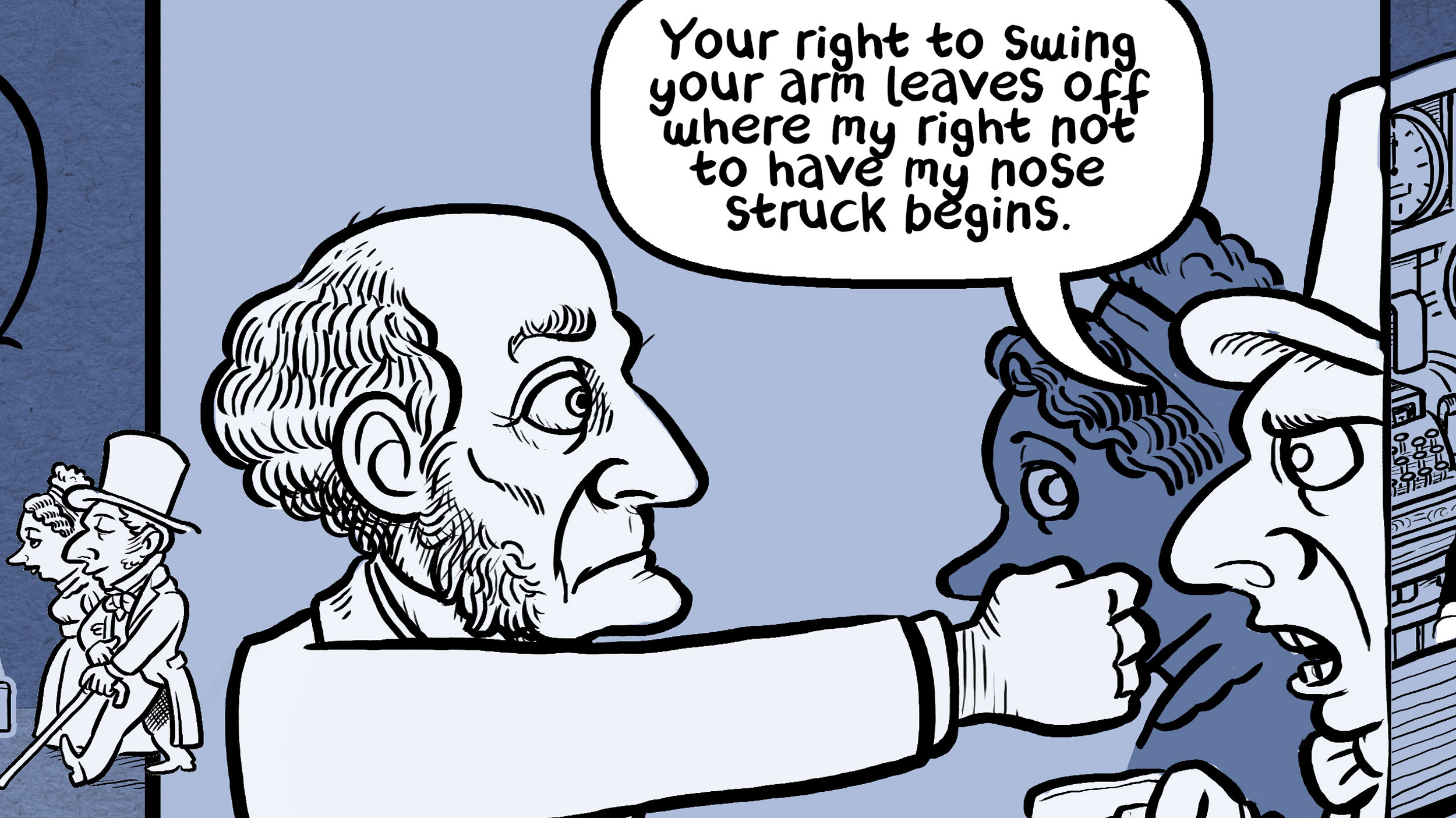

Consider, for example, John Stuart Mill’s formulation of the harm principle in his influential 1859 essay “On Liberty”: “The only purpose for which power [i.e., law] can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” [J. S. Mill, On Liberty (Kitchener, ed. 2001) (1859), at p. 13. For an overview of Mill’s harm principle, see David Brink, “Mill’s Moral and Political Philosophy”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, § 3.1 (2022).] The logic of Mill’s harm principle can be restated as follows: “Your personal liberty to swing your fist ends just where my nose begins.” [As an aside, the source of this popular refrain has been traced back to an oration delivered in 1882 by John B. Finch, who was the Chairman of the Prohibition National Committee in the 1880s. SeeGarson O’Toole, “Your Liberty to Swing Your Fist Ends Just Where My Nose Begins”, Quote Investigator (2011), https://perma.cc/6S9G-UPJ8 (https://quoteinvestigator.com/2011/10/15/liberty-fist-nose/).]

Moreover, Mill’s harm principle can, in turn, be traced to Adam Smith, who defines “justice” as restraint from harming others in his 1759 treatise The Theory of Moral Sentiments: “Mere justice is, upon most occasions, but a negative virtue, and only hinders us from harming our neighbor.” [For a survey of Smith’s conception of justice, see James R. Otteson, “Adam Smith on Justice, Social Justice, and Ultimate Justice”, Social Philosophy & Policy, Vol. 34 (2017).] But if Coase’s conception of harms is correct–if harms are indeed a reciprocal problem–then Smith’s conception of justice and Mill’s formulation of the harm principle are both incoherent, or (again) in the words of Coase: “We are dealing with a problem of a reciprocal nature. To avoid the harm to B would inflict harm on A.” [Coase 1960, p. 2.]

Is it possible to separate Coase’s economic analysis of reciprocal harms from morality and politics? Although the primary concerns of Coase’s original “cattle trespass parable” are the definition and allocation of property rights [cf. Elodie Bertrand, “The Three Roles of the ‘Coase Theorem’ in Coase’s Works”, European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Vol. 17 (2010), at p. 979: “Coase … clearly distinguishes the ethical problem of responsibility [i.e., moral blame] from the economic one”], at the same time property rights also have an inescapable moral dimension. [See, e.g. Lawrence C. Becker, “The Moral Basis of Property Rights”, Nomos, Vol. 22 (1980).] As a result, Coase’s picture of reciprocal harms does indeed have radical implications not only for economics and law but also for ethics and politics.

What are these implications? As my mentor Guido Calabresi taught me many years ago, instead of trying to assign blame or adjudicate who the wrongdoer of any given harm is, moral and political philosophers (and law professors like me!) should turn to economics and try to figure out who the “cheaper cost avoider” is.