We revisited Adam Smith’s fourth and final exception to free trade in my previous post. In summary, the father of economics makes a limited exception for trade barriers that are already on the books. Specifically, if the removal of such pre-existing trade restrictions would cause mass unemployment at home, then “freedom of trade should be restored only by slow gradations, and with a good deal of reserve and circumspection” (Wealth of Nations, IV.ii.40). In other words, Smith makes a temporary humanitarian exception for workers in protected industries.

But at the same time, although Smith concedes that opening protected industries to free trade in one fell swoop might wreak havoc at home, in the next two paragraphs of Book IV, Chapter 2 of The Wealth of Nations (paragraphs 41 & 42) he gives two concrete reasons why this disruption “would in all probability … be much less than is commonly imagined …” (ibid.). One is that labor markets are able to adjust rapidly to new conditions; the other involves the concept of absolute advantage, or in the immortal words of Adam Smith:

“… all those manufactures, of which any part is commonly exported to other European countries without a bounty, could be very little affected by the freest importation of foreign goods. Such manufactures must be sold as cheap abroad as any other foreign goods of the same quality and kind, and consequently must be sold cheaper at home. They would still, therefore, keep possession of the home-market, and though a capricious man of fashion might sometimes prefer foreign wares, merely because they were foreign, to cheaper and better goods of the same kind that were made at home, this folly could, from the nature of things, extend to so few that it could make no sensible impression upon the general employment of the people. But a great part of all the different branches of our woollen manufacture, of our tanned leather, and of our hardware, are annually exported to other European countries without any bounty, and these are the manufactures which employ the greatest number of hands. The silk, perhaps, is the manufacture which would suffer the most by this freedom of trade, and after it the linen, though the latter much less than the former.” (Wealth of Nations, IV.ii.41)

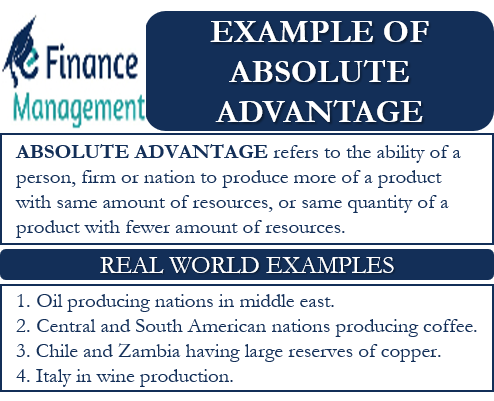

Here, Smith is singling out those unprotected industries that are already exporting products to foreign markets. To appreciate the genius of Smith’s argument, ask yourself, Why are firms in those unprotected industries able to export their goods abroad in the first place? Simply put, because they enjoy an “absolute advantage” in their respective markets, i.e. because they are able to produce goods more efficiently or cheaply than their competitors overseas. But if this is the case, then firms in those unprotected industries have nothing to fear from free trade — their products will continue to enjoy an absolute advantage in the home market!

What about Smith’s second argument for free trade: the ability of labor markets to adjust quickly to new conditions? As it happens, this is one of the most powerful arguments in favor of free trade ever made. We will take a closer look at it in my next post …

Pingback: The aftermath of the Seven Years’ War and Adam Smith’s defense of natural liberty | prior probability

Pingback: Recap of Adam Smith’s exceptions to free trade | prior probability

Pingback: Adam Smith’s finest chapter | prior probability