Previously, I described David Hume’s restatement of John Tillotson’s anti-transubstantiation argument in the form of a logical syllogism. In summary, Hume’s syllogism is this: there is no direct evidence that transubstantiation really occurs during the sacrament of Communion; instead, the only evidence we have that this doctrine might be true are some second-hand statements during the Patristic period, such as the sermons of Saint Augustine. Second-hand hearsay evidence, however, is always weaker or less reliable than direct evidence; therefore, transubstantiation cannot be true. But as I noted at the end of my previous post, this syllogism is incomplete, for Messrs Hume and Tillotson fail to consider any of the standard exceptions to the hearsay rule.

By way of illustration, the Federal Rules of Evidence (see here or here) recognize no less than 23 exceptions to the hearsay rule, including excited utterances, business records, and death-bed or dying declarations. Do any of these hearsay exceptions apply to the problem of transubstantiation? As it happens, there are at least three exceptions to the hearsay rule that might be applicable to the case at hand: statements in ancient documents; market reports and commercial publications; and statements in learned treatises, periodicals, and pamphlets. (For reference, see Rules 803(16), 803(17), and 803(18) of the Federal Rules of Evidence.)

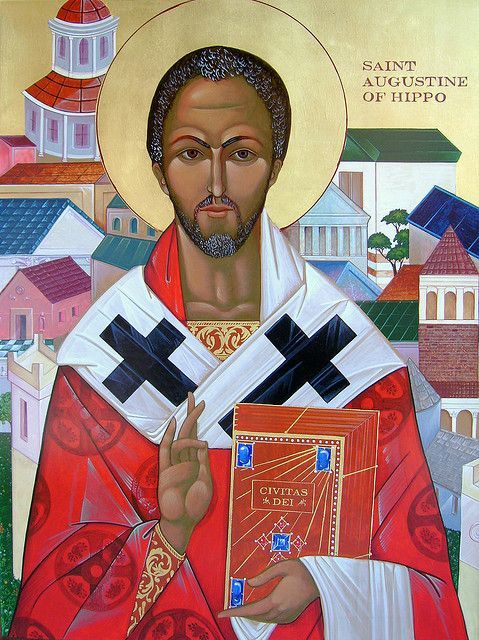

Consider, for example, the collection of sermons of Saint Augustine of Hippo (pictured below) published under the title “Sermons 230-270B on the Liturgical Seasons.” Specifically, in Sermon 234 (418 A.D.) Saint Augustine declares, without citing any supporting evidence, that the bread consecrated in the Eucharist becomes the body of Christ: “The faithful know what I’m talking about; they know Christ in the breaking of bread. It isn’t every loaf of bread, you see, but the one receiving Christ’s blessing, that becomes the body of Christ.” Is Augustine speaking metaphorically here, or is he being literal? Either way, along with Ambrose (AD 340–397), Jerome (347–420), and Pope Gregory I (540–604), Augustine (354–430) is considered one of the Great Church Fathers, so this sermon could easily fall under the exception for an ancient document or a learned treatise — or perhaps even a commercial publication!

But that said, just because a particular piece of evidence regarding transubstantiation — such as a statement in an ancient sermon by a Church father — would be admissible in a court of law under one of the exceptions to the hearsay rule does not by itself mean that transubstantiation is true. We still have to weigh the evidence (i.e. decide how trustworthy it is), draw reasonable inferences from it, and make up our own minds. In my next post, I will turn to another religious figure, the Rev Thomas Bayes (!), and explain why we should (contra Hume and Tillotson) start any discussion of transubstantiation by assigning a 0.5 probability to the possibility that this doctrine might be true.

Pingback: Transubstantiation and the principle of indifference or equal priors | prior probability