Act I, scene i of “Hume in the Library of Babel”

In my previous post, I posed a crazy thought-experiment: What if David Hume were to find himself in Jorge Luis Borges’ imaginary “Library of Babel”? But what does this imaginary world look like? Here is the first paragraph of Borges’ short story The Library of Babel:

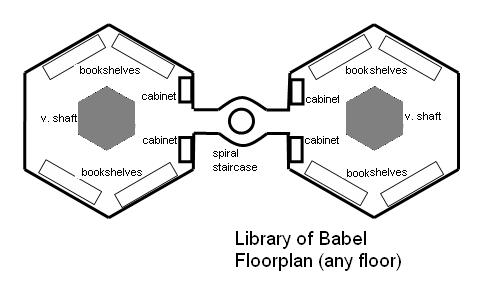

The Universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries. In the center of each gallery is a ventilation shaft, bounded by a low railing. From any hexagon one can see the floors above and below—one after another, endlessly. The arrangement of the galleries is always the same: Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon’s six sides; the height of the bookshelves, floor to ceiling, is hardly greater than the height of a normal librarian. One of the hexagon’s free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first—identical in fact to all. To the left and right of the vestibule are two tiny compartments. One is for sleeping, upright; the other, for satisfying one’s physical necessities. Through this space, too, there passes a spiral staircase, which winds upward and downward into the remotest distance. In the vestibule there is a mirror, which faithfully duplicates appearances. Men often infer from this mirror that the Library is not infinite—if it were, what need would there be for that illusory replication? I prefer to dream that burnished surfaces are a figuration and promise of the infinite. . . . Light is provided by certain spherical fruits that bear the name “bulbs.” There are two of these bulbs in each hexagon, set crosswise. The light they give is insufficient, and unceasing. [ellipsis in the original]

Act I, scene 1 of our Borges-Hume morality play thus begins with the setting: Borges’ description of an “infinite” library. This imaginary world consists of an indefinite number of interlocking hexagons. According to Borges, each hexagon contains a ventilation shaft, a circular stairwell, four walls of bookshelves, and two passages to other identical hexagons. (On either side of each passage is a latrine and sleep pod.) By way of illustration, Jamie Zawinski (via JWZ) presents a simple visual blueprint of the Library’s hexagonal design:

Zawinski’s intriguing illustration visualizes just two hexagon book galleries—that is, two out of an almost infinite number of such book-laden hexagons. What might an entire wing or floor of these hexagons look like? Below is another rendering of the Library by Jamie Zawinski:

In other words, Borges not only describes the “changeless everyday legality” of the library’s bee-like hexagonal design (Tzvetan Todorov, quoted in Kripal 2010, p. 104); he also dissolves the boundaries between the imaginary and the real (cf. Kripal 2010, p. 105), for the universal Library can actually be imagined! Or in the words of Jeffrey Kripal (2010, p. 2), Borges’ library “call[s] us out of our rationalist denials into a more spacious and generous Imagination.” In short, the infinite library is an impossible possibility.

(For additional visualizations of Borges’ Universal Library, see Jonathan Basile, Tar for Mortar: “The Library of Babel” and the Dream of Totality, Punctum Books (2018), pp. 21-32, as well as William Goldbloom Bloch, The Unimaginable Mathematics of Borges’ Library of Babel, Oxford University Press, (2008), pp. 93-103.)

Now, returning to my original question, how would a bibliophile like David Hume react were he to find himself among the infinite hexagons of this Universal Library? Wouldn’t this imaginary world represent an allegorical Heaven to such an erudite and bookish Enlightenment thinker like Hume?

To be continued …

Pingback: Borges’ paradox | prior probability

Pingback: The axioms of Borges’ Library of Babel | prior probability