Act I, scene ii of “David Hume in the Library of Babel”

My previous post went over the first paragraph of Jorge Luis Borges’ The Library of Babel, which describes the setting of the story: an “infinite” library consisting of an indefinite number of interlocking hexagons. The second paragraph of the story introduces our narrator:

Like all the men of the Library, in my younger days I traveled; I have journeyed in quest of a book, perhaps the catalog of catalogs. Now that my eyes can hardly make out what I myself have written, I am preparing to die, a few leagues from the hexagon where I was born. When I am dead, compassionate hands will throw me over the railing; my tomb will be the unfathomable air, my body will sink for ages, and will decay and dissolve in the wind engendered by my fall, which shall be infinite. I declare that the Library is endless. Idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are the necessary shape of absolute space, or at least of our perception of space. They argue that a triangular or pentagonal chamber is inconceivable. (Mystics claim that their ecstasies reveal to them a circular chamber containing an enormous circular book with a continuous spine that goes completely around the walls. But their testimony is suspect, their words obscure. That cyclical book is God.) Let it suffice for the moment that I repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is any hexagon and whose circumference is unattainable. [parenthetical in the original]

Notice that the narrator is unnamed. We don’t even know his or her gender or precise age. All we know is that he (or she) must be an elderly person (for he is “preparing to die”) who has spent his entire life searching in vain for a specific book, a tome that will unlock all the secrets of the Universal Library: “the catalog of catalogs”!

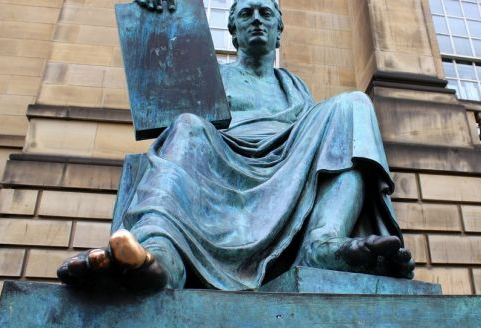

For my part, I like to imagine our unnamed narrator as the Scottish Enlightenment figure David Hume. Why? For several reasons. One point of comparison is that Hume and the narrator of Borges’ story both died a short distance from where they were born. (Hume died in the New Town section of Edinburgh on 25 August 1776 and was born in nearby Lawnmarket on the Royal Mile on 7 May 1711, while the narrator is “preparing to die … a few leagues from the hexagon where [he] was born.”)

Another parallel is that Hume, like our unnamed narrator, had also travelled great distances when he was young. (Among the places Hume had visited during his lifetime were Paris, Turin, and Vienna.) But the most significant analogy between Hume and the narrator is their religious skepticism. To the point, the narrator of Borges’ story is skeptical of mystical revelations regarding the existence of a mysterious circular chamber containing a single, god-like circular book. The narrator even tells us that their testimony is “suspect” and their words “obscure.” In other words, the narrator’s critique of these mystical claims sounds a lot like David Hume’s famous argument against miracles!

To be continued …

Pingback: Borges’ paradox | prior probability

Pingback: The axioms of Borges’ Library of Babel | prior probability