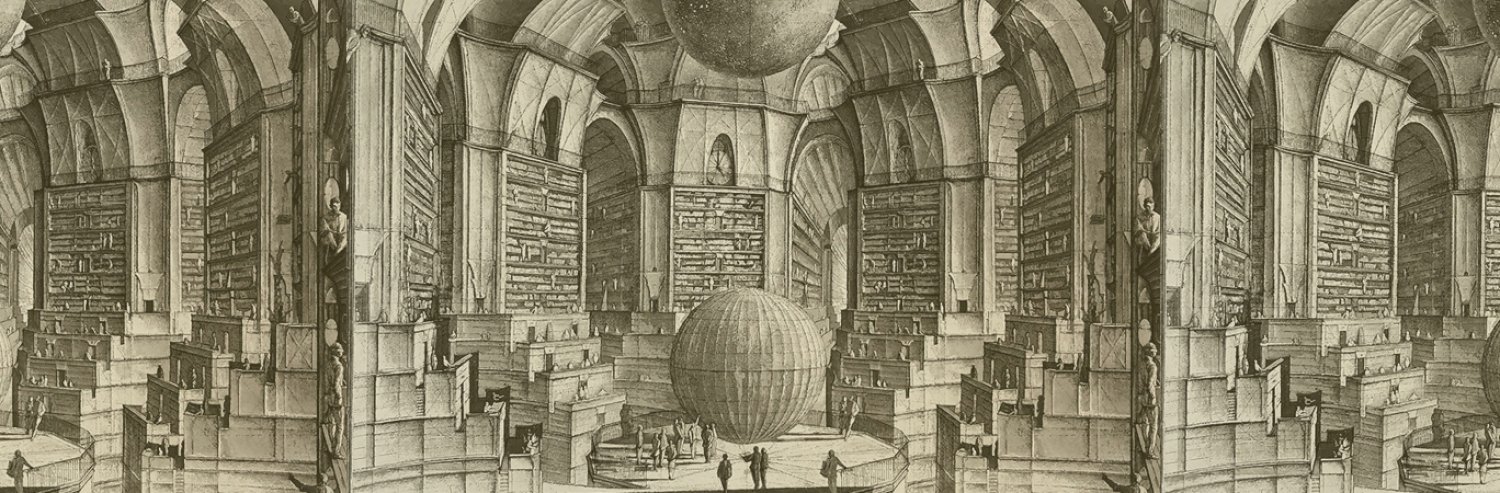

Act I, scene iii of “David Hume in the Library of Babel”

My previous two posts have revisited the first two paragraphs of Jorge Luis Borges’ The Library of Babel. Today, I will go over the third paragraph of the story, where the narrator, who in my retelling could be David Hume, describes the logic of the Universal Library:

Each wall of each hexagon is furnished with five bookshelves; each bookshelf holds thirty-two books identical in format; each book contains four hundred ten pages; each page, forty lines; each line, approximately eighty black letters. There are also letters on the front cover of each book; those letters neither indicate nor prefigure what the pages inside will say. I am aware that that lack of correspondence once struck men as mysterious. Before summarizing the solution of the mystery (whose discovery, in spite of its tragic consequences, is perhaps the most important event in all history), I wish to recall a few axioms. [parenthetical in the original]

The logical structure of the Universal Library is thus simple yet mysterious: every hexagon contains the same number of bookshelves (five); each bookshelf holds the same number of books (32); and every book in every hexagon shares the same number of pages (410 pp.), the same number of lines on each page (40), and approximately the same number of letters on each line of each page (80). In addition, the narrator reports that “[t]here are also letters on the front cover of each book” but that “those letters neither indicate nor prefigure what the pages inside will say.”

As an aside, this discrepancy between the book covers and the books, in turn, reminds me of Charles Fort’s “parable of the peaches” as recounted Jeffrey Kripal’s Authors of the Impossible. In brief, when Fort was a child he was required to work at his father’s grocery store on Saturdays, where he was assigned the rote task of peeling of the labels from the cans of fruits and vegetable of another dealer and pasting on his father’s private labels instead. One day, however, “he found himself with pyramids of cans, but only peach labels left in his sticky armory.” (Kripal 2010, p. 102) Or in Fort’s own words: “I pasted the peach labels on the peach cans, and then came to apricots. Well, aren’t apricots peaches? I went on, mischievously, or scientifically, pasting the peach labels on cans of plums, cherries, string beans, and succotash. I can’t quite define my motive, because to this day it has not been decided whether I am a humorist or a scientist.” (Fort 1932, p. 850, quoted in Kripal 2010, p. 102)

So, just as the peach labels in Charles Fort’s parable did not correspond with non-peach contents on many of the canned goods, the titles of the book covers in the Universal Library do not necessarily correspond with the contents of each book, making the search process in this imaginary infinite archive even more of an uphill battle, more of a mystery. As it happens, mysteries and mathematics appear side-by-side at the end of this third introductory paragraph, where the narrator of the story juxtaposes the deep spiritual concept of mystery with the mathematical and logical concept of axioms. Or in the words of Borges’ unnamed narrator, “Before summarizing the solution of the mystery (whose discovery, in spite of its tragic consequences, is perhaps the most important event in all history), I wish to recall a few axioms.” What are these imaginary axioms?

To be continued …

Pingback: Borges’ paradox | prior probability

Pingback: The axioms of Borges’ Library of Babel | prior probability