As I mentioned in a previous post, I see some possible parallels between Downes v. Bidwell, one of the infamous “Insular Cases” decided in 1901, and President Donald J. Trump’s controversial “Liberation Day” tariffs. Although Downes v. Bidwell involved an act of Conrgess (the Foraker Act of 1900), while the Trump tariff cases involve presidential executive orders, one important parallel is that both sets of cases involve trade.

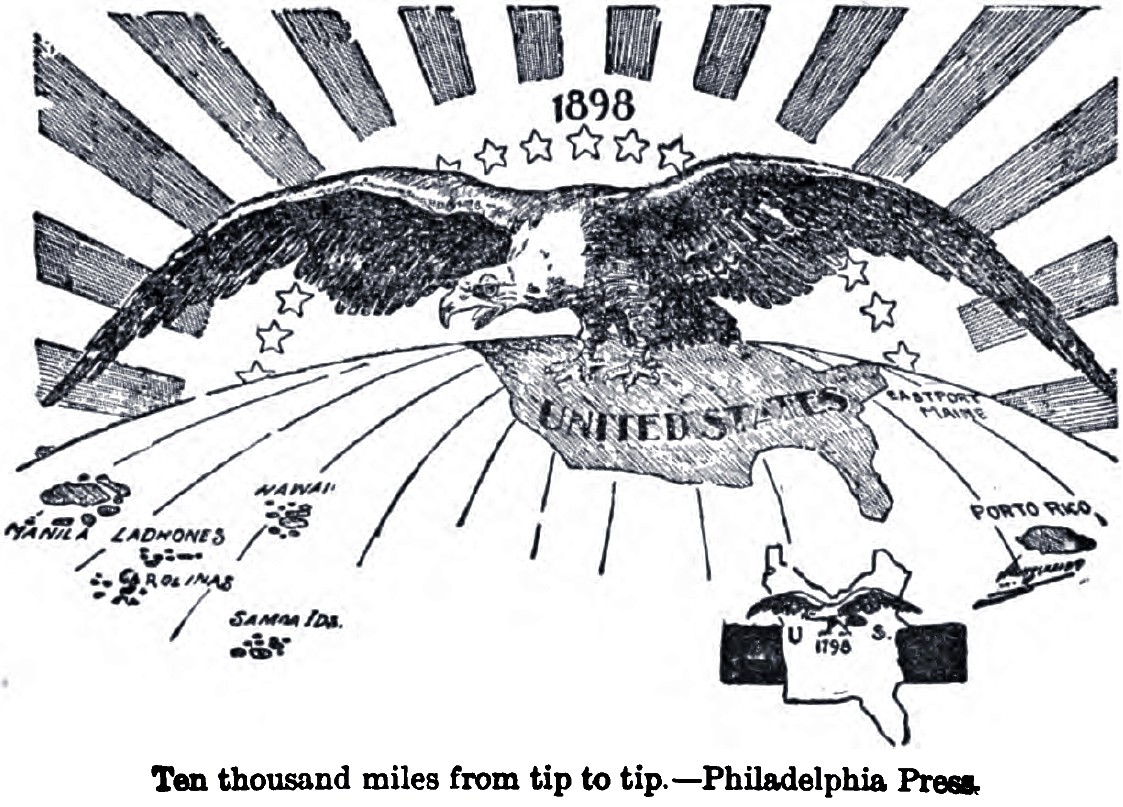

In Downes v. Bidwell, the plaintiff (Samuel Downes) had imported a shipment of oranges from Puerto Rico, a newly-acquired U.S. territory, into the Port of New York. When his shipment arrived, the U.S. customs inspector for the port of New York (George Bidwell) imposed import duties on Downes’ shipment under the Foraker Act of 1900. (Among other things, the Foraker Act established a civilian government for Puerto Rico, which had been acquired by the United States in 1898 and was under U.S. military rule until the passage of this law. In addition, the Foraker Act also levied customs on all imports from Puerto Rico into the United States.)

Downes then challenged Bidwell’s action under the Uniformity Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 1), which declares that “all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” Since the Foraker Act singled out Puerto Rico for import duties, Downes argued the Foraker Act was unconstitutional. Puerto Rico, however, was a territory, not a State, and the Territory Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article IV, Section 3, Clause 3) gives Congress the “Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.”

In other words, Downes v. Bidwell involves two conflicting constitutional provisions. On the one hand, the Uniformity Clause in Article I creates a level economic playing field inside the United States by requiring all internal excise taxes, import duties, etc. to be the same “throughout the United States,” but at the same time the Territory Clause in Article IV appears to give Congress plenary power over U.S. territories, including the power to impose import duties. How do we resolve this conflict?

In addition to this particular tension, the Insular Cases as a whole present the following open-ended constitutional question writ large: even if Article I trumps Article IV (i.e. even if the Congress is bound by the rules set forth in Article I when making rules and regulations for U.S. territories), was Puerto Rico legally part of the United States at the time this case was decided, or was it “foreign in a domestic sense” as the Supreme Court would enigmatically rule in 1901? Suffice it to say that a similar internal constitutional conflict and open-ended question will emerge when we take a closer look at the current batch of Trump tariff cases in my next post.