N.B.: This is Part 5 of my series on “Critical thinking in the age of A.I.”

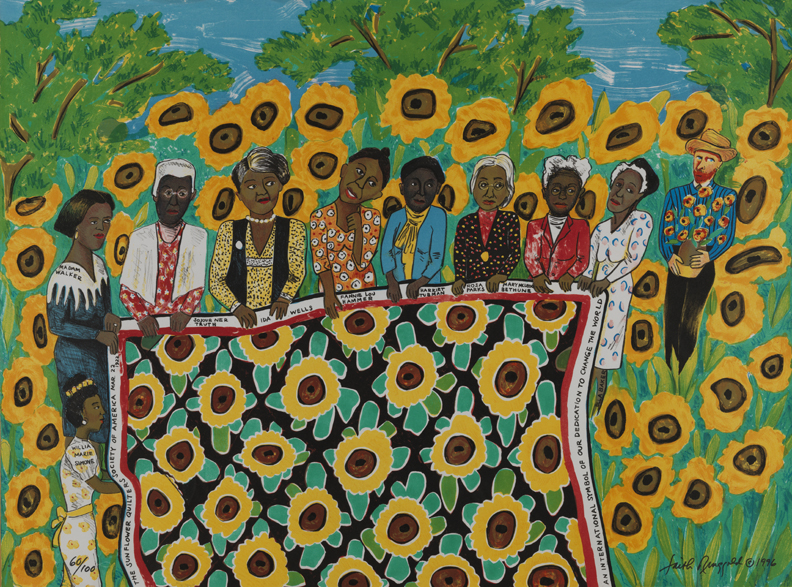

Yesterday (see here), I responded to John McPeck’s critique that there are no general thinking skills; today, I will respond to the other objections to the theory, pedagogy, and practice of critical thinking that I had surveyed in a previous post, including those by Alston (2001), Martin (2002), Paul (1981), and Thayer-Bacon (2000). Broadly speaking, the common thread tying together these sundry criticisms is “dissatisfaction with focusing [exclusively] on the logical analysis and evaluation of reasoning and arguments” (Hitchcock 2024, 12.2). Instead, these critics see critical thinking as “a social, interactive, personally engaged activity like that of a quilting bee … rather than as an individual, solitary, distanced activity symbolized by Rodin’s The Thinker” (ibid.).

For me, one of the most memorable and moving examples of this more social or communal approach to critical thinking is bell hook’s innovative “engaged pedagogy” method of teaching: in her introductory course on black women writers, students are required to write an autobiographical paragraph about an early racial memory and then to read their work aloud to the class as whole. (hooks 1994: 84) The goal of hook’s communal approach to critical thinking is thus to affirm “the uniqueness and value of each voice” in the class by “creating a communal awareness of the diversity of the group’s experiences” (Hitchcock 2024, 12.2).

On this note, one of the advantages of my own Humean/Bayesian approach to critical thinking (see here) is that this approach can be practiced by groups as well as by individuals. In fact, the original inspiration for my Humean/Bayesian approach is the common law jury of lore, where a group of six or 12 ordinary people are chosen at random and asked to evaluate the evidence presented by the parties in the case. Although a single judge acts as a gatekeeper both before and during the trial (overseeing the jury-selection process and deciding which pieces of evidence are relevant and which are “privileged”, “prejudicial”, or otherwise inadmissible), it is the jury as a whole, meeting outside the presence of the judge, who decides how much weight to assign to the evidence.

Both my common law jury model and bell hooks’ communal approach to critical thinking highlights another limitation of large language models like ChatGPT: although these models share a communal aspect, since they are trained on massive datasets created by a large number of people, at the same time they are designed to be used by a single user only. But is ChatGPT an inherently individualized and atomistic tool, isolating (and perhaps alienating) its users from each other and the world at large, or is there any way to make ChatGPT usage more of a communal, social, or shared experience (like, say, Wikipedia)? I will conclude my series on “ChatGPT and critical thinking” in my next post.

Work cited: bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, New York & London: Routledge (1994).

Pingback: *Your brain on ChatGPT* | prior probability

Pingback: *Your brain on ChatGPT* | prior probability