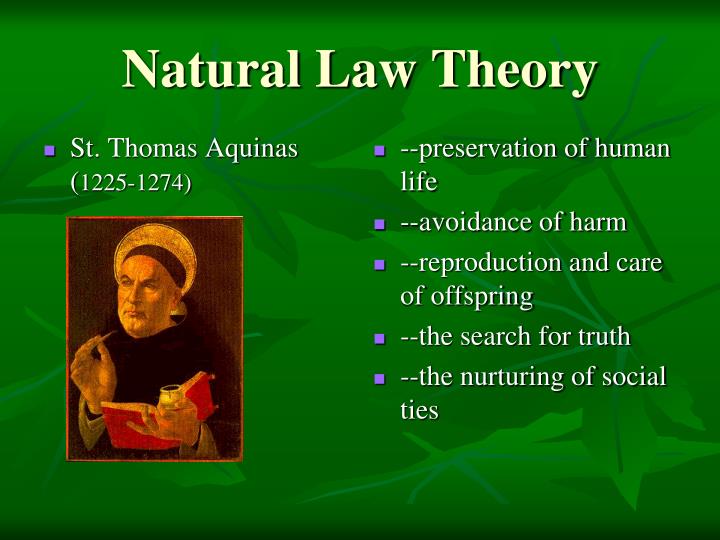

In my previous post, I began my review of the late Alasdair MacIntyre’s 2023 essay On Having Survived the Academic Moral Philosophy of the 20th Century by noting “the pervasiveness of disagreement”, not just among moral philosophers as MacIntyre does, but also among constitutional law professors and legal philosophers more generally. I also mentioned that MacIntyre’s alternative approach to moral philosophy is informed by the natural law tradition of Thomas Aquinas. Today, then, I will pick up where I left off by describing MacIntyre’s natural law approach to philosophy.

In summary, the natural law approach to legal philosophy begins by asking, What is the goal of law? Why do we have law in the first place? By the same token, MacIntyre’s natural law approach to moral philosophy begins by asking, and I quote, “What is it to be a good human being?” (A minor quibble, but I would reformulate MacIntyre’s question by asking, What does it mean to lead a good life?) MacIntyre then proceeds in paragraph 15 of his essay to identify “four sets of goods” that are needed to be good person, i.e. to lead a good life:

First, without adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter, physical exercise, education, and opportunity to work no one is likely to be able to develop his or her powers—physical, intellectual, moral, aesthetic—adequately. Second, everyone benefits from affectionate support by, well-designed instruction from, and critical interaction with family, friends, and colleagues. Third, without an institutional framework that provides stability and security over time a variety of forms of association, exchange, and long-term planning are impossible. And fourth, if an individual is to become and sustain … himself as an independent rational agent, … he needs powers of practical rationality, of self-knowledge, of communication, and of inquiry and understanding.

Notice that with MacIntyre’s natural law formulation of the good life, basic survival goods are not enough for one to flourish. In addition to such basic goods as food, clothing, and shelter to ensure our physical survival, we also need three more types of goods: (1) emotional, especially love and affection from our family and friends; (2) institutional or legal, i.e. a stable legal environment so we can trade with others and make plans; and last but not least, (3) and epistemological, i.e. critical thinking skills. (As a college professor, I especially like the last item on this list of natural law goods: practical rationality and critical thinking more generally.)

After formulating this laundry list of goods, MacIntyre draws the following conclusion in the 16th paragraph of his essay: “there are standards independent of our feelings, attitudes, and choices by which we may judge whether this or that [action or decision] is choiceworthy, whether this or that is good to choose, to do, to be, to have, to feel.” But that said, I can’t help but notice two big blind spots, two gaping holes, in MacIntyre’s approach to ethics: he falls into what I like to call the natural law fallacy, and he fails to define key terms.

Simply put, natural rights are supposed to be timeless and universal, but where does natural law itself come from? Specifically, who says that MacIntyre’s four sets of goods, and only those four, are a necessary or sufficient condition for leading a good life? And who is supposed to provide them? Alas, MacIntyre himself never tells us where his “four sets of goods” come from, or who is supposed to provide them. Nor does he bother to define such critical terms as adequate, friend, institutional, or practical rationality.

So, is there any way to escape these two natural law traps? Is there any way of locating the ultimate source of natural law or of defining key terms? I will address these questions in my next post.

Pingback: Alasdair MacIntyre’s natural law bait and switch | prior probability

Pingback: On having survived MacIntyre’s essay on moral philosophy | prior probability

Pingback: Alasdair MacIntyre postscript | prior probability

Pingback: End-of-year review: my other 2025 projects | prior probability