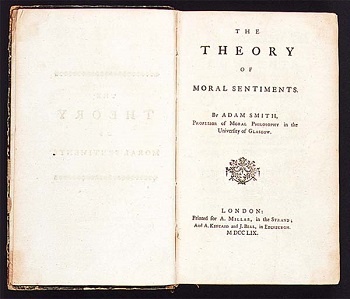

I began my previous post by asking, Who (or what?) is the “impartial spectator” in Adam Smith’s first magnum opus, The Theory of Moral Sentiments? (This is just one of the many open “Adam Smith problems” my colleague and friend Salim Rashid and I address in our ongoing survey of unresolved or contested Smith problems.) As it happens, Daniel Klein, Nicholas Swanson, and Jeffrey Young (2025) have just published a new paper in Econ Journal Watch making a strong case for why Smith’s ideal observer is none other than God or some other make-believe godlike entity they call Joy. Either way, according to Klein et al., this imaginary being is “a universal beholder” who boasts “superhuman knowledge and universal benevolence” (Klein, Swanson, & Young 2025, p. 297).

Alas, even if we were to assume for the sake of argument that this theistic interpretation of Smith’s ideal observer is true, three tough questions immediately spring to mind. First off, why do Klein, Swanson, and Young further complicate Smith’s imaginary being by taking away some of his godlike powers and then changing his name and gender and calling him “Joy” instead of just plain, old “God”? (See ibid., pp. 297-298.) Secondly, if Smith’s impartial spectator really is a deity or godlike figure, why are there — by Klein et al.’s own count no less — at least eight separate passages in Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments in which the impartial spectator specifically does not refer to a deity? (See, for example, ibid., at p. 307.) And what, in turn, is the source of this anomaly?

For their part, Klein, Swanson, and Young concede that Smith’s writings about the impartial spectator are unclear at best: “If [the] ‘impartial spectator’ rises to God/Joy, why didn’t Smith provide a direct, concise statement saying that?” (Ibid., p. 298.) There are two possibilities: (a) either Smith was being purposely evasive on this point, or (b) it is Smith’s convoluted theory of morality that itself is confusing. (Or in the alternative, some combination of a and b might be true.) But which of these two possibilities is most likely the correct one? To their credit, Klein et al. identify several reasons why Smith was being purposely evasive or “esoteric” in a Leo Straussian sense. (See ibid., pp. 321-322.) Stay tuned, I will entertain their intriguing thesis (i.e. that Smith was being unclear on purpose) in my next post as well as explain why their Straussian conjecture is most likely wrong.

Pingback: A second-order question about Adam Smith’s impartial spectator | prior probability

Pingback: One last question for Klein, Swanson, and Young | prior probability