Nota bene: this is the eighth of a series of blog posts on “the paradox of politics”.

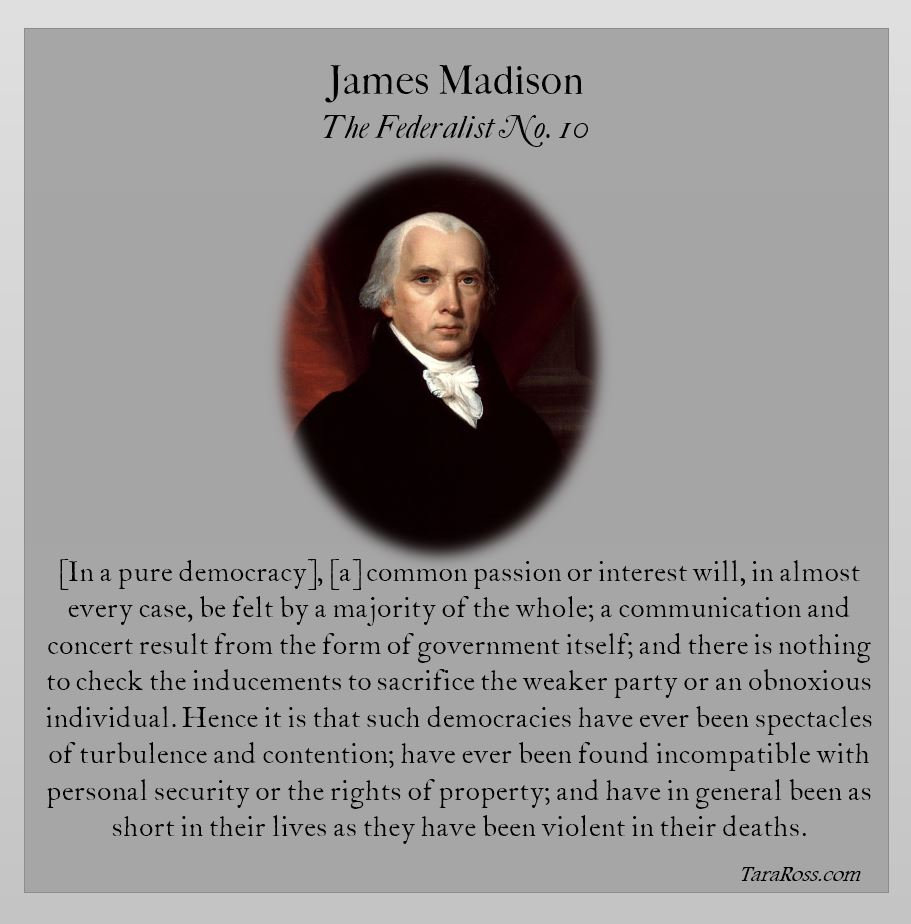

“By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” –James Madison, Federalist #10

By now, the identity of X should be obvious to all: he is none other than James Madison. Although this founding father has many achievements to his name — he was elected the fifth president of the United States, served as secretary of state to the fourth president (Thomas Jefferson), drafted the bill of rights, and was the unofficial secretary of the constitutional convention of 1787 — his greatest legacy and claim to fame was his co-authorship (with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton) of the Federalist Papers.

In my previous post, I extended Madison’s famous definition of factions (quoted above) in Federalist #10 to encompass Hume’s emphasis on public opinion as the invisible social glue that keeps governments, whether despotic or democratic, in power. After all, what is a faction but a group of people with a shared opinion about some matter of private or public interest? In short, the relationship between factions and public opinion is a symbiotic one.

Either way, whether our focus (like Madison’s) is on factions or (like Hume’s) on public opinion, let’s recall why factions are so dangerous. They are, in the eloquent words of Madison, “mortal diseases” that generate nothing but “instability, injustice, and confusion.” (pp. 321-322) But at the same time, factions will always arise in a free society: “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires.” (p. 322) I like to call this tension between factions and liberty Madison’s dilemma: how do we control factions — and avoid the tyranny of public opinion — without getting ridding of liberty?

One possible solution is the election of a man like George Washington, a great statesman who is able to balance the interests of competing factions and bend public opinion toward the common good, but as Madison correctly notes, don’t hold your breath: “It is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” (p. 323)

Madison’s solution to the problem of factions — and to the tyranny of public opinion more generally — is a structural one: regardless of who is in power, if a faction or opinion consists of less than a majority, ordinary politics will keep such activist groups, however vocal, in check. Or in the immortal words of James Madison: “relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote.” (p. 323) Although such vocal activist groups might be able to stir up some trouble, they lack the votes to carry out their nefarious schemes: “[They] may clog the administration, [they] may convulse the society; but [they] will be unable to execute and mask [their] violence under the forms of the Constitution.” (ibid.)

But what happens when a majority is included in a faction? That is, what happens when public opinion is in agreement with the nefarious plans of some specific faction? It is here where Madison’s full genius is on full display. His proposed solution is so elegant and original — and yet so counterintuitive — that I will quote it in full:

“Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked that, where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonorable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary.” (p. 325)

In other words, Madison’s ingenious solution to the problem of factions — and to the tyranny of public opinion — is … wait for it … more factions, more opinions! To paraphrase Mao, let a thousand factions bloom! Why? Because the more factions and niche opinions there are, the more difficult it will be for any one specific faction or opinion to crowd out and dominate the rest.

But what does this Madisonian solution to the problem of factions have to do with the paradox of politics, i.e. with the tension between law and liberty? Everything! After all, all laws are restrictions of liberty, but under Madison’s “extend the sphere” solution, no law will be enacted unless a sufficient number of factions are able to join forces in support of such law. But in the process of joining forces and forming strategic alliances, the leaders of these factions — i.e. the demagogues and opportunists who shape public opinion — will have to compromise in order to secure enough support to get their preferred policies and measures enacted.

In short, it is this Madisonian process of compromise, the give-and-take of negotiation and alliance-formation, that keeps the ever-present dangers of factions and public opinion in check. But is Madison’s ingenious solution to the paradox of politics still relevant to our world? Even before the election (and re-election!) of Donald J. Trump, our national government has grown to monstrous proportions, a monetary Leviathan indeed. According to the Department of Treasury (see here), for example, the federal government spent $6.75 trillion in fiscal year 2024, or almost one-fourth (23%) of our entire GDP (gross domestic product)! I will conclude my series on the paradox of politics with some closing thoughts in my next post.

Pingback: The paradox of politics: part 2 | prior probability