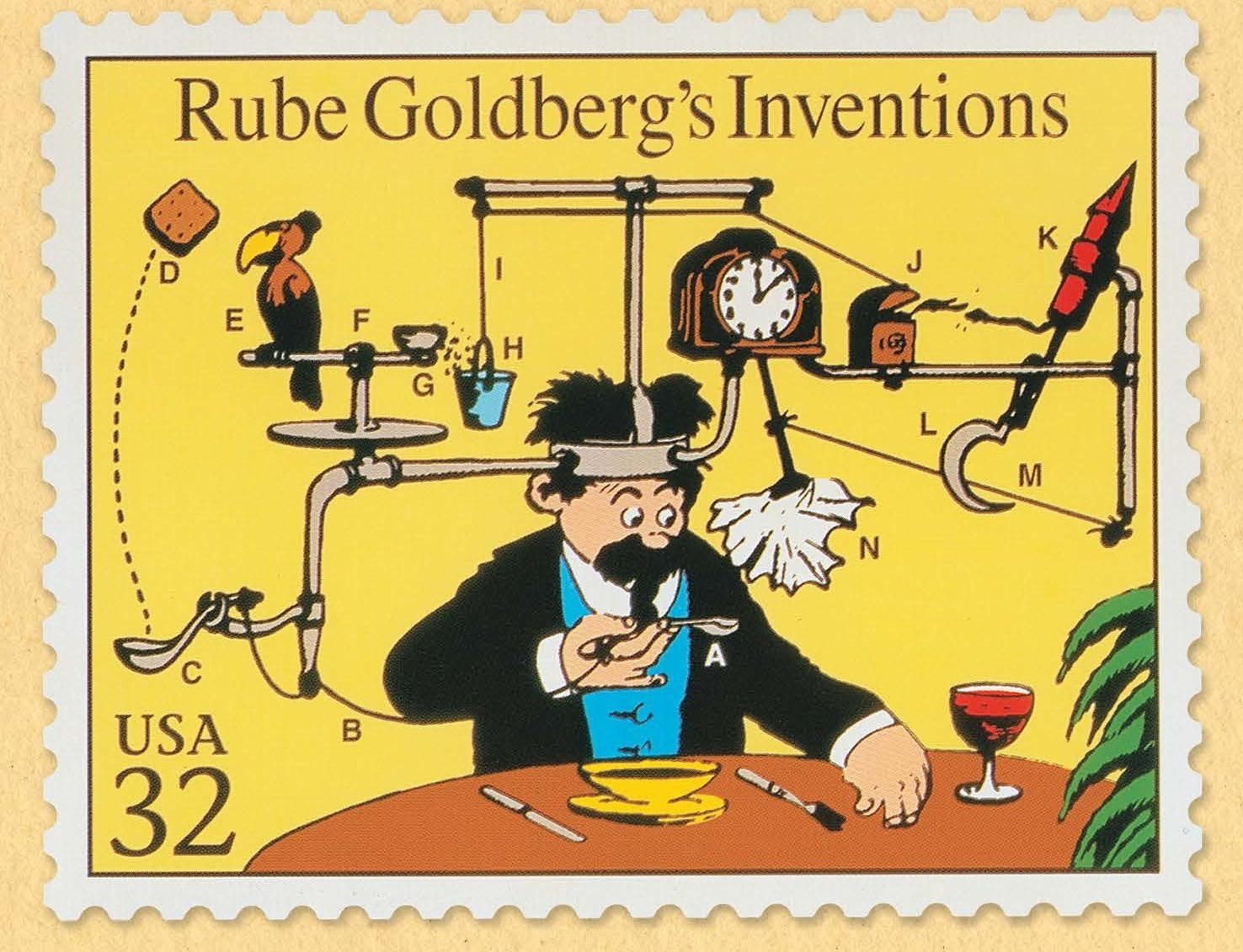

Nota bene: a Rube Goldberg machine is an elaborate chain-reaction-type contraption intentionally designed to perform a simple task in a comically overcomplicated way.

I concluded my previous post by asking whether the man within the breast and the impartial spectator in Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) are two separate and distinct entities or whether they are just two different ways of saying the same thing. For reference, let’s call the first possibility “the two-tiered impartial spectator thesis” and let’s call the second possibility “the unitary impartial spectator thesis“.

Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, that Adam Smith indeed proposed a two-tiered system of moral scrutiny in which the man within the breast (the agent) acts as the representative or agent of the impartial spectator (the principal). On one level (the ground-level, so to speak), every man, woman, and child in the world has his or her own individual “man withing the breast” somewhere deep inside them, but on another level (the sky level), there is a global, godlike, and all-seeing impartial spectator, the ultimate moral judge or ethics tribunal from which there is no appeal. If this two-tiered schema is what Smith really had in mind when he revised TMS in 1790, then notice how this method of making moral judgments actually involves three separate actors in all!

- First off, we have the main subject, a flesh-and-blood person (man, woman, or child) who is deciding on some course of action or inaction, as the case may be.

- Next, we have the subject’s “man within the breast” (one’s “inner voice” or conscience), who acts as the impartial spectator’s representative.

- Last but not least, we have the man-within-the-breast’s principal, the impartial spectator, who presumably has the final say on moral matters.

How plausible is this picture, this two- or three-tiered Rube-Goldberg-like system of morality? What, for example, is the division of labor between the impartial spectator (the big man) and the man within the breast (the agent)? Perhaps the job of the imaginary big man is to act as an arbiter: he steps in and calls the shots only when the subject and the man within the breast disagree on the morality of some course of action. Or maybe the role of the impartial spectator is to monitor collusion. On this view, the big man comes into play when the subject and the man within the breast try to collude together to justify some wrongful act.

Alas, this two-tier picture of moral judgment has a blind spot: why should we listen to the impartial spectator in the first place? Also, why do we need two separate entities — the impartial spectator and the man within the breast; the big man and his agent — to pass judgment on the morality of our actions? I will conclude with some final thoughts in my next post …