“To protect the social compact from being a mere empty formula, therefore, it silently includes the undertaking that anyone who refuses to obey the general will is to be compelled to do so by the whole body. This single item in the compact can give power to all the other items. It means nothing less than that each individual will be forced to be free.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau [1]

Thus far, we have defined Rousseau’s godlike “general will” (see here), and we have clarified how this concept could be put into practice (here). Today, I will explain why Rousseau’s general will is one the most seductive but dangerous ideas in all of political philosophy. First off, recall what Rousseau means by the general will and how this concept would work in reality. To recap, Rousseau’s general will is the popular expression of the common good — nothing more, nothing less — and so long as the eligible voters (all?, most?) are “adequately informed” and do not communicate with each other before voting (no free speech?), whatever a majority of the voters decide on will be an expression the general will.

But not so fast, you might say. Aside from the many practical problems with Rousseau’s radical political scheme — what does it mean, for example, to be “adequately informed”, and how can people be informed at all if they are not allowed to communicate with each other? — what about Rousseau’s biggest blind spot of all: the tyranny of the majority? How does Rousseau solve this timeless problem?

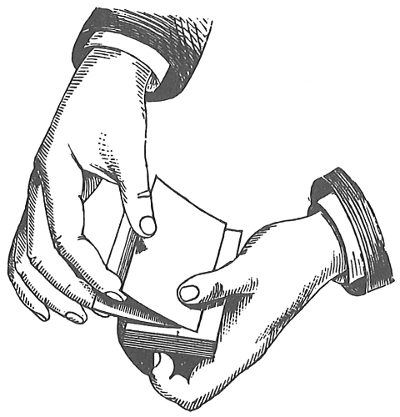

Here is where Rousseau’s evil genius is on full display: the Swiss philospher performs an Orwellian sleight of hand; he waves the equivalent of an intellectual magic wand to make the age-old problem of majority rule disappear altogether. For Rousseau, true freedom is not the freedom to pursue one’s private interests; it’s obedience to the general will! The tyranny of the majority is thus a non sequitur or logical impossibility. Why? Because by complying with the dictates of the general will, one is ultimately obeying oneself.

But Rousseau doesn’t just redefine the meaning of freedom. He also employs his new definition of what it means to be free to justify the elimination of “factions” and “partial associations”. Recall Rousseau’s definition of the general will: “If, when an adequately informed people deliberates, the citizens were to have no communication among themselves, the general will would always result from the large number of small differences, and the deliberation would always be good.” [2] Here is the entire passage:

“If, when an adequately informed people deliberates, the citizens were to have no communication among themselves, the general will would always result from the large number of small differences, and the deliberation would always be good. But when factions, partial associations at the expense of the whole, are formed, the will of each of these associations becomes general with reference to its members and particular with reference to the State. One can say, then, that there are no longer as many voters as there are men, but merely as many as there are associations. The differences become less numerous and produce a result that is less general. . . .

“In order for the general will to be well expressed, it is therefore important that there should be no partial society in the State, and that each citizen give only his own opinion.” [3]

In other words, factions and partial associations are, by definition, contrary to the general will and must therefore be banned. But as Madison warned us long ago: “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires.” [4] Do you now see why Rousseau’s ideas are so dangerous, even more risky and sinister than Plato’s proposed system of philosopher-kings? With Plato, at least one can argue that his Republic is not meant to be taken seriously, that Plato meant for us to read his work with irony. [5] Rousseau, however, is dead serious. The Swiss philosopher would not only destroy freedom of speech (recall that the voters under his system would not be allowed to communicate with each other before voting); he would also eliminate factions and partial associations.

To conclude (for now), a strong case can be made that it is Jean-Jacques Rousseau, not Plato or Marx, who is the true villain of modern political theory. Why? Because both Plato and Marx advocated for their preferred despots, whether it be a dictatorship led by workers or one led by public intellectuals, in the open. Rousseau, by contrast, conceals his authoritarianism with his seductive talk of the general will and the common good.

Nevertheless, we are not yet done with Rousseau, not by a mile, for a major 20th century political philosopher would not only try to rehabilitate the general will by dressing up Rousseau’s dangerous idea in classical liberal garb; his work now dominates the Anglo-American sphere. (To be continued …)

[1] Rousseau, Section 7 of Book I of The Social Contract (“The Sovereign”).

[2] Rousseau, Section 3 of Book II of The Social Contract (“Whether the General Will Can Err”), reprinted in Cohen 2018, p. 273.

[3] Ibid., emphasis added.

[4] Federalist #10.

[5] See, e.g., part one of Søren Kierkegaard’s classic On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates (1861), available here: https://dn710008.ca.archive.org/0/items/kierkegaard-soren-the-concept-of-irony/Kierkegaard%2C%20S%C3%B8ren%20-%20The%20concept%20of%20irony.pdf

Pingback: Rawls preview | prior probability

Pingback: Beware of Rousseauian wolves in Rawlsian clothing | prior probability

Pingback: Christmas season update | prior probability