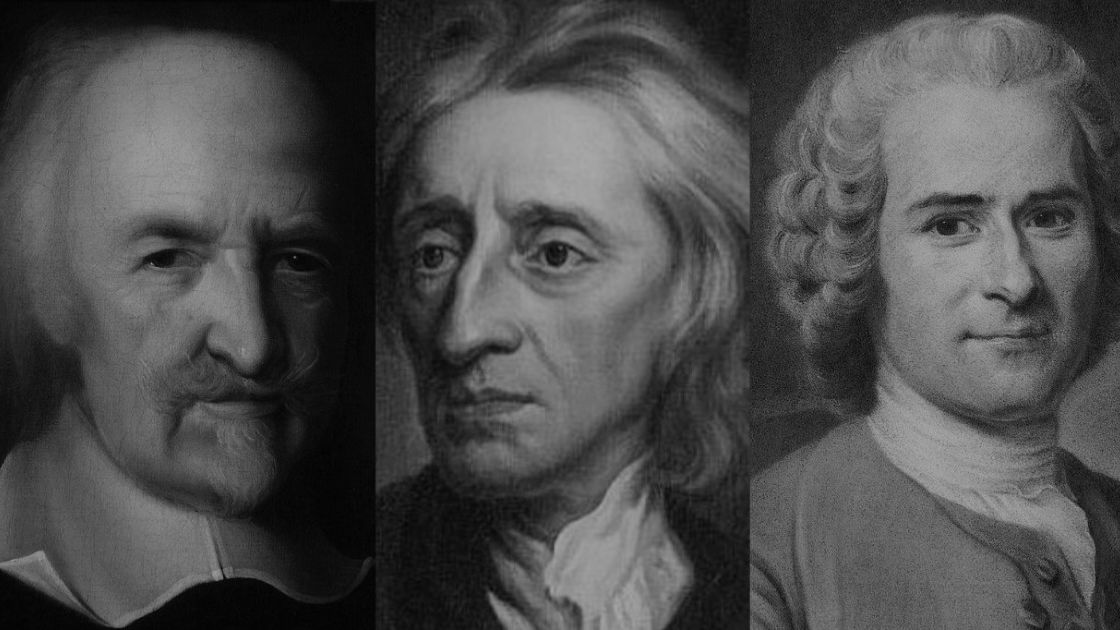

This past weekend I concluded my series on the paradox of politics, which I began in October of this year. Among the many political theorists we surveyed were Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacque Rousseau, all of whom are deservedly famous for developing a strand of political philosophy known as social contract theory. Although this influential political theory has many variants (see here, for example), a common thread is a fictional collective agreement or “social compact” in which individuals in a state of nature consent, either implicitly or explicitly, to surrender some, or even all!, of their natural liberties and freedoms to the government in exchange for protection, order, and the maintenance of property rights. Although social contract theory has played a pivotal role in modern political philosophy, does good political philosophy make for bad contract law? More specifically, what happens when we view social contract theory from a purely legal or common law lens? What, in a word, is the legal status of the social contract, and does the answer to this question depend, in turn, on whose social contract we are talking about? Would any of the fictional social contracts postulated by Hobbes, Locke, or Rousseau, for instance, be legally valid or enforceable under modern contract law doctrines, and if so, what would constitute a material breach of the social contract, and what would the proper legal remedy be? These are just some of the questions that I will explore starting tomorrow (17 December).