[Alternative title: “The Dearth of Nations: How Government Subsidies Make Us Poorer”]

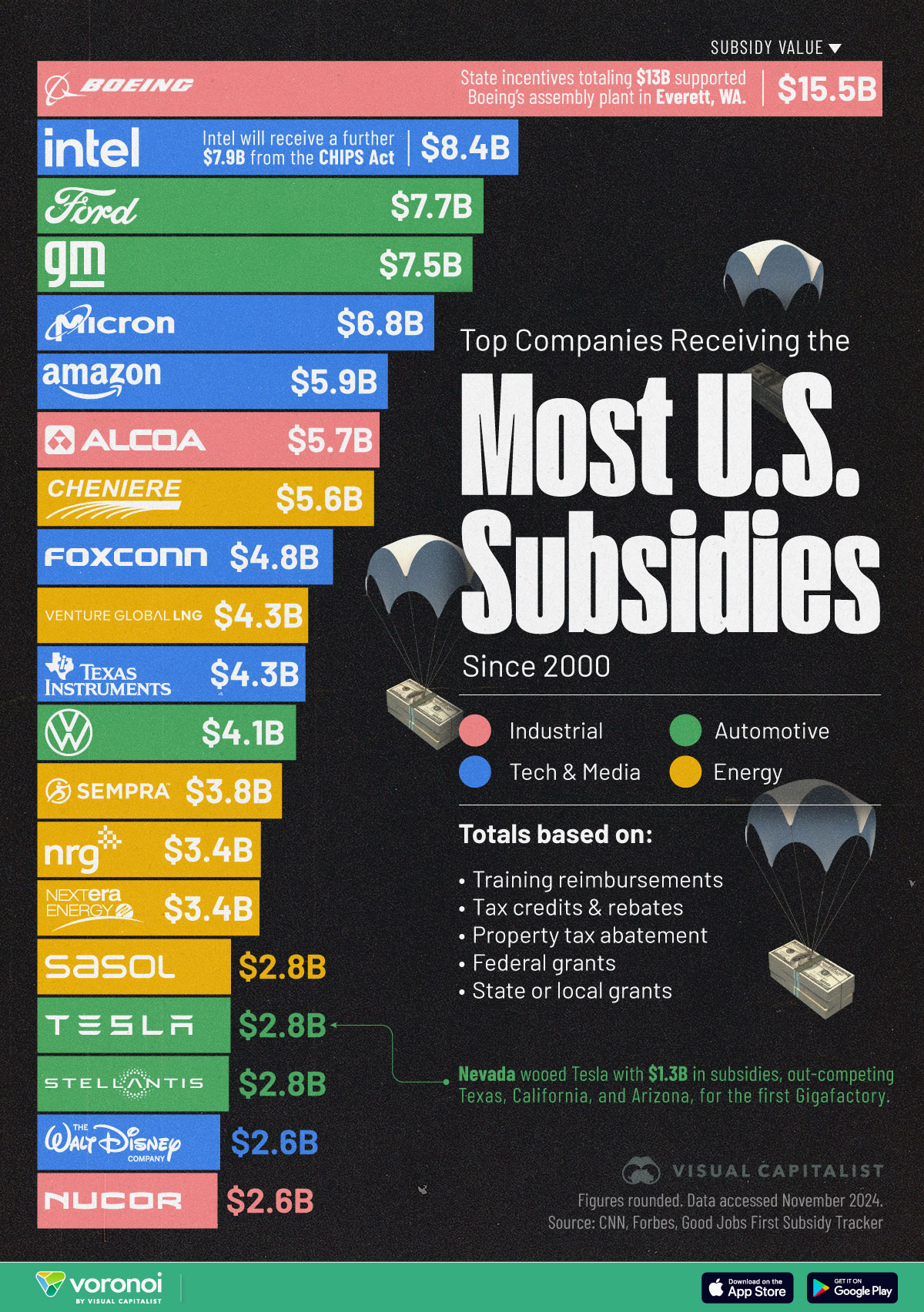

Adam Smith takes dead aim at yet another mercantilist policy in Chapter 5 of Book IV of The Wealth of Nations, a foolish and futile scheme that continues up to this day (see, for example, the infographic pictured below): crony capitalism in the form of “bounties upon exportation”, i.e. government subsidies that are paid directly to potent and powerful and well-connected producers in certain strategic industries like (in Smith’s day) grain. Smith tells us right off the bat what the mercantilist rationale of such bounties upon exportation is — to promote exports in certain industries in order to obtain a favorable balance of trade:

“Bounties upon exportation are, in Great Britain, frequently petitioned for, and sometimes granted to the produce of particular branches of domestic industry. By means of them our merchants and manufacturers, it is pretended, will be enabled to sell their goods as cheap, or cheaper than their rivals in the foreign market. A greater quantity, it is said, will thus be exported, and the balance of trade consequently turned more in favour of our own country.” (WN, IV.v.a.1)

But as the Scottish philosopher-economist explains in the first half of Chapter 5 (see especially Para. 24), bounties upon exportation are almost always injurious to a country’s overall economic health. Although Smith makes a limited exception for “bounties upon the exportation of British-made sail-cloth, and British-made gun-powder,” two goods that Smith says are necessary for national defense (WN, IV.v.a.36), such government subsidies are otherwise counterproductive. More specifically, bounties upon exportation make nations poorer in three ways: they misallocate capital, impose a double-burden on taxpayers, and distort prices:

1. Misallocation of capital. To begin, Smith observes how government subsidies divert the flow of capital. Simply put, bounties prop up business firms and entire industries that would not otherwise survive:

“Those trades only require bounties in which the merchant is obliged to sell his goods for a price which does not replace to him his capital, together with the ordinary profit; or in which he is obliged to sell them for less than it really costs him to send them to market.” (WN, IV.v.a.2)

In other words, bounties subsidize trades and industries where the cost of production exceeds the value of returns. As a result, the aggregate effect of government subsidies is to inhibit economic growth and development. Why? Because bounties cause capital assets to be misallocated into unproductive industries instead of being put to better or more productive uses, or in the immortal words of Adam Smith, “The effect of bounties, like that of all the other expedients of the mercantile system, can only be to force the trade of a country into a channel much less advantageous than that in which it would naturally run of its own accord.” (WN, IV.v.a.3)

2. Double-taxation. Next, Smith turns to the example of the corn bounty to show more generally how bounties and subsidies are a form of double taxation, i.e. a massive redistribution of income from the public to the beneficiaries of these mercantilist policies. Taxpayers must not only fund the cost of the government subsidy program itself; the public at large will end up paying higher prices overall for the goods being subsidized:

“The corn bounty, it is to be observed, as well as every other bounty upon exportation, imposes two different taxes upon the people; first, the tax which they are obliged to contribute in order to pay the bounty; and secondly, the tax which arises from the advanced price of the commodity in the home market, and which, as the whole body of the people are purchasers of corn, must, in this particular commodity, be paid by the whole body of the people. In this particular commodity, therefore, this second tax is by much the heavier of the two.” (WN, IV.v.a.8)

3. Distortion of the price signal. As the last sentence in the passage quoted above indicates, bounties (especially bounties upon exportation) distort prices. How so? When bounties are tied to exports of certain goods (such as grain or corn), such bounties end up reducing the supply of those goods at home and thus increasing their price:

“The extraordinary exportation of corn, therefore, occasioned by the bounty, not only, in every particular year, diminishes the home, just as much as it extends the foreign, market and consumption, but, by restraining the population and industry of the country, its final tendency is to stunt and restrain the gradual extension of the home market; and thereby, in the long run, rather to diminish, than to augment, the whole market and consumption of corn.” (WN, IV.v.a.8)

As it happens, Smith has much more to say about the grain market: the second half of Chapter 5 of Book IV of his magnum opus contains a “Digression concerning the Corn Trade and Corn Laws”. (WN, IV.v.b) Why does Smith devote so much attention to the grain trade? By some accounts, this trade represented a large chunk (if not the largest share) of the total trade of the British Isles. (See, e.g., Dennis Baker, “The Marketing of Corn in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century: North-East Kent”, Agricultural History Review, Vol. 18, No. 2 (1970), pp. 126-150, available here.) Suffice it to say, then, we will take a closer look at Smith’s digression in my next post.