Translation: The Adam Smith Colonial Problem (I respectfully beg the indulgence of my loyal readers for the Germanic title of this particular blog post. It is an intentional reference to the original so-called “Das Adam Smith Problem” — if you know, you know! Footnotes are below the fold.)

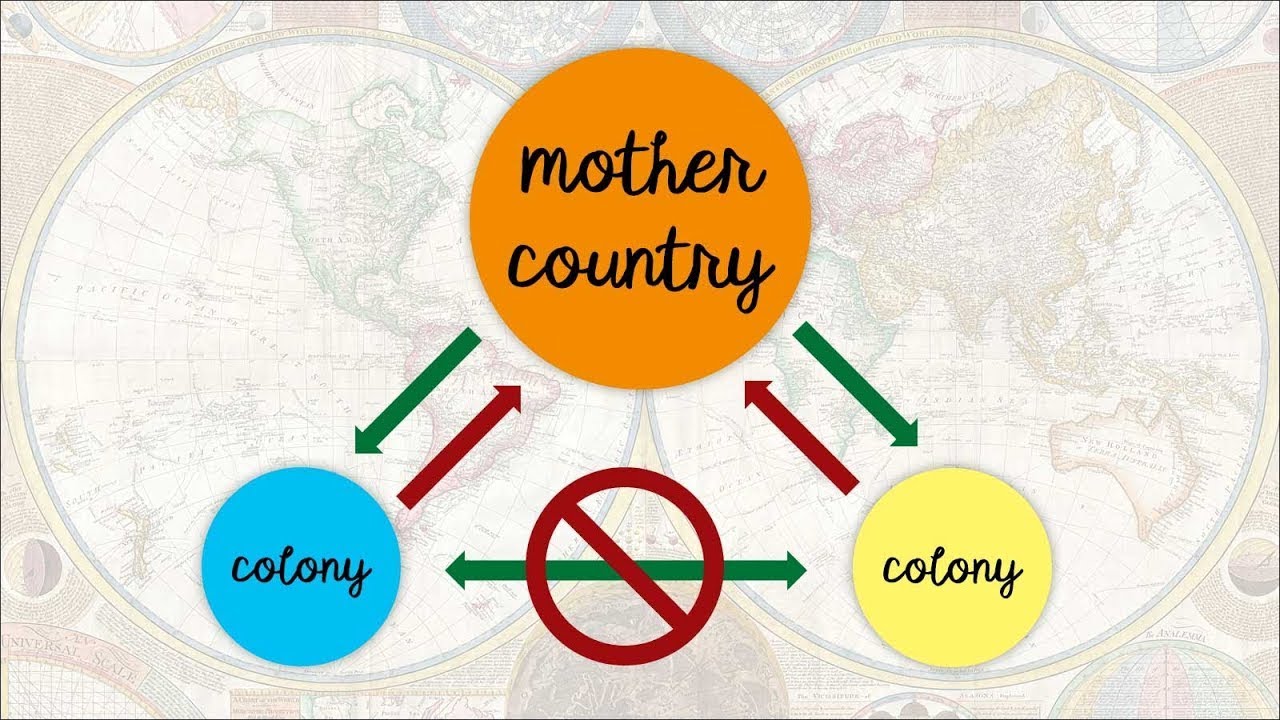

“NO TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION” was the chief rally cry of the North American rebels calling for independence in 1776 — the year The Wealth of Nations was published — but what if King George III of Great Britain had granted his North American (and West Indian) colonies representation in the British Parliament? Towards the middle of Part 3 of Chapter 7 of Book IV of his magnum opus (available here; scroll down to “Part Third”), Adam Smith drops the following bombshell:

“The Parliament of Great Britain insists upon taxing the colonies; and they [the colonies] refuse to be taxed by a Parliament in which they are not represented. If to each colony, which should detach itself from the general confederacy, Great Britain should allow such a number of representatives as suited the proportion of what is contributed to the public revenue of the empire, in consequence of its being subjected to the same taxes, and in compensation admitted to the same freedom of trade with its fellow-subjects at home; the number of its representatives to be augmented as the proportion of its contribution might afterwards augment; a new method of acquiring importance, a new and more dazzling object of ambition would be presented to the leading men of each colony.” (WN, IV.vii.c.75)

Wait, what?! Is Smith proposing giving the North American colonies full representation in Parliament? Is he really presenting a political solution to the brewing rebellion in North America? Yes, he is, and to follow up on my previous post, it is my Number One “Top Adam Smith Play” in this chapter. But was Smith being serious when made this bold proposal, or was he being ironic? One of my colleagues, Dan Klein (2023), has made a strong case that Smith did not mean this radical political proposal to be taken seriously. Other Smith scholars, by contrast, have taken Smith’s proposed constitutional union at face value.[1] Who’s right?

On the one hand, Klein (2021) has shown how certain passages in some of Smith’s essays, lectures, and other works lend themselves to an esoteric reading, one in which we cannot take what Smith is saying at face value but must read between the lines to arrive at Smith’s true meaning.[2] For Klein (2023), Smith’s radical proposal should also be read this same esoteric way. Among other things, Klein emphasizes just how impractical such a constitutional union would have been given the time-consuming nature of travel across the Atlantic Ocean at the time.

But on the other hand, we have Smith’s own eloquent words: “There is not the least probability that the British constitution would be hurt by the union of Great Britain with her colonies.” (WN, IV.vii.c.77) That statement, taken at face value, sure sounds like a full-throated endorsement of a grand constitutional union between Britain and her North American colonies. Also, for what it’s worth, after Smith mentions in passing that “[t]here is not the least probability that the British constitution would be hurt by the union of Great Britain with her colonies,” he adds:

“That constitution [i.e. the grand union between North American and Great Britain], on the contrary, would be completed by it, and seems to be imperfect without it. The assembly which deliberates and decides concerning the affairs of every part of the empire, in order to be properly informed, ought certainly to have representatives from every part of it.” (WN, IV.ii.c.77)

Smith further suggests that the North American colonies might become even more prosperous than Great Britain and that the “seat of the empire” might move overseas from London to North America: “… in the course of little more than a century, perhaps, the produce of America might exceed that of [Great Britain’s]. The seat of the empire would then naturally remove itself to that part of the empire which contributed most to the general defence and support of the whole.” (WN, IV.ii.c.79) Are these prophetic passages in The Wealth of Nations mere rhetorical hyperbole? At that time (1776), the three largest cities in British North America by population were Boston (around 16,000 souls), New York City (25,000), and Philadelphia (30,000 to 38,000).[3] By way of comparison, the population of London at that same time was several orders of magnitude larger: around 750,000 souls.[4] For what it’s worth, the 20th-century Smith scholar W. R. Scott reports:

“… after the publication of The Wealth of Nations, [Adam Smith] was consulted in 1778 by Alexander Wedderburn, Solicitor-General in Lord North’s administration, and he replied in a Memorandum endorsed ‘Smith’s Thoughts on the Contest with America Feby. 1778’ in which he, ‘as a solitary philosopher’ recommends a constitutional union with America with ‘the most perfect equality’ between both parts of the Empire ‘enjoying the same freedom of trade and sharing in their proper proportions both in the burden of taxation and in the benefit of representation…. The leading men of America, being either members of the general legislature of the Empire, or electors of those members would have the same interest to support the general government of the Empire which the members of the British legislature and their electors have to support the particular government of Great Britain.'” (Scott 1935, p. 84, footnote omitted)

So, was Smith serious? If so, why didn’t he also propose a constitutional union between one or both of her two most recently-acquired colonial prizes, Bengal and Quebec?[5] Why not unify Britain and Ireland, for that matter?[6] Either way, I will conclude on this note: a political association between Britain and North America was not as far-fetched as my colleague and friend Dan Klein would have us believe, for there was a recent historical precedent for such a bold political union: the two “Acts of Union” of 1707 — one ratified by the Parliament of Scotland in March 1707, the other by the Parliament of England shortly thereafter — putting into effect the Treaty of Union signed on 22 July 1706, the treaty that formally united the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland into a single Kingdom of Great Britain.

Nota bene: I will conclude my review Part 3 of Chapter 7 of Book IV of The Wealth of Nations on Monday.