Correction (8/30): Our colleague and friend Alain Alcouffe has pointed out to us a possible error about the identity of “Dr Smith” in the Voltaire passage quoted below. In brief, the Dr Smith Voltaire is referring may not be Adam Smith at all. Instead, the author of Candide could be referring to a Robert Smith, the author of a 1738 treatise on optics (available here). We will do some additional digging and report back soon.

Below is an excerpt from Chapter 9 (“Das Voltaire-Problem”) of my forthcoming survey of open Adam Smith problems with Salim Rashid (footnotes are below the fold):

“Among the most illustrious Enlightenment figures Adam Smith met and perhaps befriended during his grand tour years was Voltaire, and according to one account (Muller 1993, p. 15), Smith made a good impression on the famed Lumière. After meeting Smith, Voltaire wrote, ‘This Smith is an excellent man! We have nothing to compare him, and I am embarrassed for my dear compatriots.’[1] But what did Smith think of the great Voltaire?

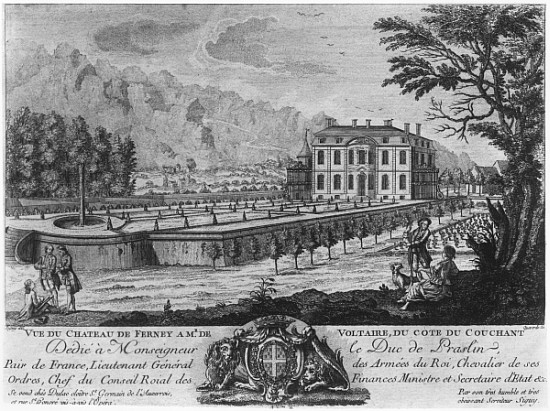

“No doubt, Smith must have admired the celebrated Lumière even before their encounters in 1765, for Voltaire is mentioned many times in Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments.[2] But why did Smith go out of his way to meet him in 1765, and what did they discuss? Though all accounts of Adam Smith’s time in the city-state of Geneva—i.e. when his meetings with Voltaire took place—are extremely sparse, we know that the Scottish moral philosopher left Toulouse and travelled to Geneva in the fall of 1765,[3] and we also know that during his time in the little republic he became personally acquainted with Voltaire, who at the time lived in nearby Ferney.[4] [N.B.: Voltaire’s estate at Ferney is pictured below.] But aside from the opportunity of arranging one or more meetings with Voltaire, why did Smith decide to visit Geneva at all instead of heading straight to Paris, where he would reside for the remainder of his grand tour? What did he hope to accomplish or observe there, and how long did he stay? Was Voltaire the primary purpose of Smith’s jaunt to Geneva?

“According to one hearsay account (Rae 1965/1895, p. 189), reporting what Adam Smith had told the English poet Samuel Rogers years later, in 1789, the Scottish philosopher had visited the famed lumière no less than five or six times during this period. Another hearsay account confirms Smith’s admiration—not just for Voltaire, but also for Rousseau![5] Did Smith and Voltaire talk about Rousseau? Samuel Rogers, Rae tells us, mentions two possible topics of conversation. One was ‘the Duke of Richelieu, the only famous Frenchman Smith had yet met,’[6] while the other was ‘the political question as to the revival of the provincial assemblies or the continuance of government by royal intendants.’[7]

“But this can’t be the whole story. Aside from the legendary martial exploits and sexual conquests of Louis François Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, 3rd duc de Richelieu (1696-1788), or the contemporaneous Brittany Affair (an ongoing power struggle between the chief magistrate or procureur of the local courts of Brittany, Louis-René de Caradeuc de La Chalotais (1701-1785), and the governor and royal representative of the region, Emmanuel Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, duc d’Aiguillon (1720-1780)), two additional and more immediate topics may have occupied Voltaire and Adam Smith at this time. One was the Voltaire-Needham controversy that was then playing out in real time in the fall of 1765. The other was what we call the ‘fracas at Ferney’: the Voltaire-Charles Dillon affair of December 1765. Both the Voltaire-Needham controversy and the fracas at Ferney are relevant to our Smithian inquiries because both occurred amid Smith’s visit to Geneva….”