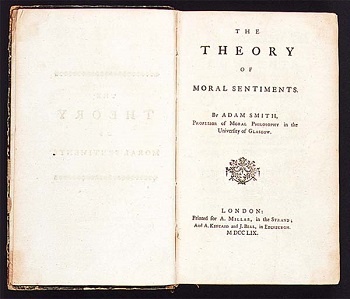

As I have mentioned in my last few posts, my colleagues Daniel Klein, Nicholas Swanson, and Jeffrey Young have published a new paper in Econ Journal Watch about one of the most original and fascinating ideas in the work of Adam Smith: the impartial spectator. According to Klein et al., the impartial spectator is a deity. To this end, they identify a trio of passages in Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) in support of their claim that the impartial spectator is a godlike being. For reference, these three specific passages from TMS are quoted in full below:

Passage #1 (294.49):

None of those systems [of virtue ethics] either give, or even pretend to give, any precise or distinct measure by which this fitness or propriety of affection can be ascertained or judged of. That precise and distinct measure can be found nowhere but in the sympathetic feelings of the impartial and well-informed spectator. (TMS, VII.ii.1.49, quoted in Klein et al. 2025, p. 304; emphasis and boldface added by Klein et al.)

Passage #2 (225.19):

Nature, which formed men for that mutual kindness, so necessary for their happiness, renders every man the peculiar object of kindness, to the persons to whom he himself has been kind. Though their gratitude should not always correspond to his beneficence, yet the sense of his merit, the sympathetic gratitude of the impartial spectator, will always correspond to it. (TMS, VI.ii.1.19, quoted in Klein et al. 2025, pp. 304-305; emphasis and boldface added by Klein et al.)

Passage #3 (215.11):

In the steadiness of his industry and frugality, in his steadily sacrificing the ease and enjoyment of the present moment for the probable expectation of the still greater ease and enjoyment of a more distant but more lasting period of time, the prudent man is always both supported and rewarded by the entire approbation of the impartial spectator, and of the representative of the impartial spectator, the man within the breast. The impartial spectator does not feel himself worn out by the present labour of those whose conduct he surveys; nor does he feel himself solicited by the importunate calls of their present appetites. To him their present, and what is likely to be their future situation, are very nearly the same: he sees them nearly at the same distance, and is affected by them very nearly in the same manner. He knows, however, that to the person principally concerned, they are very far from being the same, and that they naturally affect them in a very different manner. He cannot therefore but approve, and even applaud, that proper exertion of self-command, which enables them to act as if their present and future situation affected them nearly in the same manner in which they affect him. (TMS, VI.i.11, quoted in Klein et al. 2025, p. 305; emphasis in the original; boldface added by Klein et al.)

So, is Klein, Swanson, and Young’s interpretation correct, or are they off the mark? Is Adam Smith’s “impartial spectator” some sort of god or deity? The first two passages quoted above seem to imply that the impartial spectator is infallible, so he must be a god of some sort, but at the same time, it is worth noting that there is no explicit reference whatsoever to a deity in either of those excerpts. By a process of elimination, we are thus left with Passage #3, and if you read Klein, Swanson, and Young’s new paper for yourself, you will see that they put all of their argumentative eggs in this one basket, so to speak. Stay tuned, for I will scrutinize the third and last passage in greater detail in my next post.