A counterfactual is a statement about what would have happened if a past event had been different. It’s a “what if?” scenario, considering an alternative reality where something that actually occurred did not, or vice versa. On this note, below is an excerpt from Chapter 11 (“Counterfactual Conundrums”) of my forthcoming survey of open Adam Smith problems with Salim Rashid (emphasis added; footnotes are below the fold):

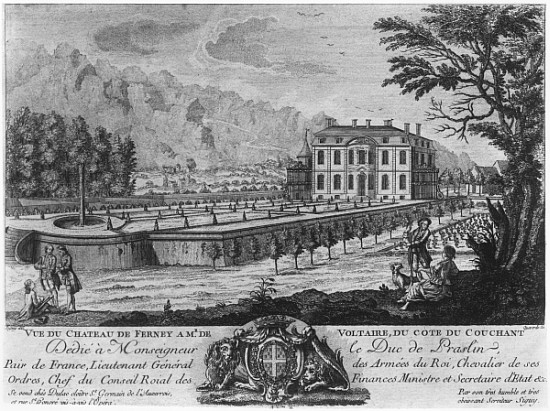

“… the buzz generated by the publication of The Wealth of Nations in 1776 would produce another major plot twist in Adam Smith’s life, an unexpected detour that would mark the close of Smith’s scholarly pursuits: his appointment as a Commissioner of Customs in the royal town of Edinburgh, a post the Scottish philosopher would hold during the remaining 12 years of his life: February 1778 to July 1790. The Scottish philosopher thus ended up spending almost as much time in the customs house (pictured below) than he did at Glasgow University, for he was thus a customs officer for almost as many years as he was a professor!

“But in the words of Walter Bagehot (1876, p. 38), given Smith’s reputation for absent-mindedness (whether real or, as we suspect, feigned) a ‘person less fitted to fill [the post of Customs Commissioner] could not indeed have easily been found.’ Worse yet, the philosopher-economist was now in charge of enforcing the very same protectionist laws that he had denounced in The Wealth of Nations. Although Smith himself never said whether or not his duties as customs officer went against personal convictions,[1] leading some Smith scholars to see no contradiction between Smith’s stirring defense of free trade and his decision to become a customs commissioner,[2] for us the cognitive dissonance is mind-blowing.

“Moreover, Smith’s stint as a customs officer was no sinecure or honorary position; by all accounts, it was a full-time job that would consume a large chunk of his waking hours.[3] Although Smith published four subsequent editions of The Wealth of Nations (1778, 1784, 1786, and 1789) and made substantial revisions and additions to the sixth and last edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1790) after his appointment as Commissioner of Customs, his day-to-day duties in the customs house would prevent him from completing any other major scholarly books or articles, including the ‘two other great works on the anvil’ that we mentioned in a previous chapter (Ch. 4).

“For us, then, this closing chapter in Smith’s life presents one major counterfactual question, what we call Das Kommissarproblem. What if Smith had never accepted this position? How would Smith have spent the final 12 years of his life? Would he have returned to academia? Would he have completed either of the ‘two other great works’ he was supposedly working on? Or would he have been content with the two magna opera he had already published? And these aren’t the only customs-house questions we have, for we have always wondered why Adam Smith, a self-confessed bookworm who had become a major literary figure, agreed to accept the position of Commissioner of Customs in the first place. Simply put, why did he give up his ongoing intellectual pursuits (for the most part) to become a glorified bureaucrat for the remainder of his life?[4] Why not say ‘no’? Was it money, prestige, intellectual fatigue, or something else that motivated Smith to say ‘yes’?

“Also, Smith published four subsequent editions of The Wealth of Nations after his appointment as Commissioner of Customs (1778, 1784, 1786, and 1789) as well as a sixth and last edition of The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1790. How did his stint in the customs house influence any of these subsequent editions of his Wealth of Nations or Theory of Moral Sentiments? And lastly, and perhaps most importantly, how did Smith resolve the cognitive dissonance between his duty as a customs officer to enforce the oppressive system of existing trade barriers on the one hand and his stirring defense of free trade and ‘natural liberty’ in his Wealth of Nations on the other?”