- Interview with Tyler Cowen, prolific author, globetrotter, and “information monster” extraordinaire.

- Interview with Alex Guerrero, political theorist and author of Lottocracy (pictured below).

- Interview with Timothy Snyder, the professor who cried wolf.

Monday medley: interviews with three professors

Coase’s fable

That is the title of the paper, available here via SSRN, that I will be presenting this weekend at the Winter Institute for the History and Philosophy of Economics at the University of Austin (UATX). My paper is an updated version of two previous paper I wrote: one titled “Coase’s Parable,” which was published in the Mercer Law Review in 2023; the other, “Modelling the Coase Theorem,” published in the European Journal of Legal Studies in 2013. In my updated paper, I revisit Ronald Coase’s cattle trespass hypothetical and explore the origins of his counter-intuitive insight that harms are a reciprocal problem, an idea that I now call “Coase’s axiom.”

Timeout: UATX Winter Institute for the History and Philosophy of Economics

This weekend, I will be attending and presenting my work on Ronald Coase, who is considered the founder of “law & economics,” at the Winter Institute for the History and Philosophy of Economics at the University of Austin (UATX), a private non-profit university founded in 2021 whose motto is “the fearless pursuit of truth.” Stay tuned. I will provide additional updates soon.

Is the social contract legally-enforceable?

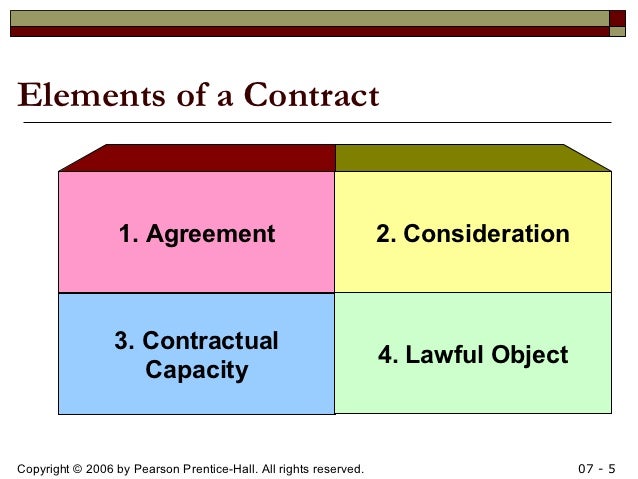

How do our Anglo-American common law principles inform social contract theory? Would any of the three fictional social contracts of Hobbes, Locke, or Rousseau, for example, be enforceable from a purely legal perspective? Recall from my previous post the four common law elements of legally-enforceable agreement: A. offer and acceptance (mutual assent), B. consideration, C. capacity, and D. lawful purpose. With this legal background in mind, below are my tentative thoughts:

A. Regarding the first element, can there really be mutual assent in the state of nature? Alas, all social contract theorists just assume the existence of voluntary mutual assent. But in truth, we really don’t know if either the offer of the social contract or its acceptance was, in fact, voluntary or, what is more likely, if they (offer/acceptance) were made under duress. After all, when you stop to think about, how can our dire situation in the state of nature — a state of war, according Hobbes and even Locke — not be a state of duress? Also, since the social contract is a pre-political instrument — it was supposedly negotiated in the state of nature — then who exactly is the “offeror”? In other words, even if there was mutual assent, the social contract looks more like a non-enforceable oath than a “contract”!

B. Next, regarding the second element, consideration is a legal doctrine that helps us distinguish legally-binding and enforceable contracts from “mere promises” or gifts, which are not enforceable, and for this crucial element to be met, each party must give up something of legal value — like money, goods, or services — to the other. In addition, a promise to refrain from acting (forbearance) is deemed something of legal value under the doctrine of consideration. In the case of the social contract, we are supposed to be giving up our natural liberty in exchange for protection from the state, but this observation begs the question, is our natural liberty in the state of nature really a God-given pre-political right (i.e. we have a moral right to enjoy our natural liberty) or is it just an empirical description of the state of nature (i.e. we can do whatever we want in the absence of a duly-established government to enforce its laws on us)? And either way, how much liberty did we really have in the state of nature?

C. Regarding the third element, capacity refers to a person’s ability to form a binding contract: they must be of sound mind amd of legal age; they must understand the terms and consequences of the agreement. But what about children and non-human animals? Does the social contract apply to them? As it happens, contract law allows minors to rescind their contracts when they reach the age of majority, but how does one opt out of a Hobbesian or Lockean or Rousseauian social contract once it comes into play? On the contrary, if there is one thing that social contract theorists of all stripes have in common it is this: they do not allow anyone the right to opt out of the social contract once it is formed!

D. Lastly, regarding the fourth element, an agreement is void and unenforceable if its purpose or subject matter is immoral, fraudulent, or against public policy, or if injures a third party. On this note, what if the so-called “social contract” were better seen, not as a legitimate deal among equals to keep the peace, but as just a glorified form of extortion: your liberty or your life!

Point of order: However the substance of the so-called “social contract” is described (i.e. as extortion or a legitimate deal), my tentative observations above are just a short sketch of a more formal paper that I am working on. In the meantime, I will conclude my series on “Social Contracts and the Law” with one last observation (for now): the term “social contract theory” is a misnomer to the extent it implies a master or single “social contract” that all social contract theorists agree on. In reality, however, it is better to use the term “social contracts” (plural), for there are as many strands of social contract theory as there are social contract theorists! As a result, instead of assuming we are dealing with one composite or master social contract, each of these proposed social contracts must be scrutinized on its own terms.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/common-law_sourcefile-1636c3563ba04d88919f87d22c4f0349.jpg)

Social contracts and the law

Is the so-called “social contract” of social contract theory a valid or legally-enforceable agreement? At common law, the four key elements of a contract are as follows:

- Offer & Acceptance (Mutual Assent): A clear proposal by one party (offeror) and an unconditional agreement to its terms by the other (offeree), showing a “meeting of the minds” or shared understanding.

- Consideration: Each party must give up something of legal value (a promise, an act, or refraining from an act) in exchange for the other’s promise or performance.

- Capacity: Parties must be legally competent (e.g., not minors, mentally incapacitated) to enter the agreement.

- Legality (Lawful Purpose): The contract’s objective must be legal and not against public policy.

What happens when we apply these four common law elements of contract law to the social contracts of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau? Stay tuned, for that is what we are going to do in my next post!

Postscript: is the social contract really a *contract*?

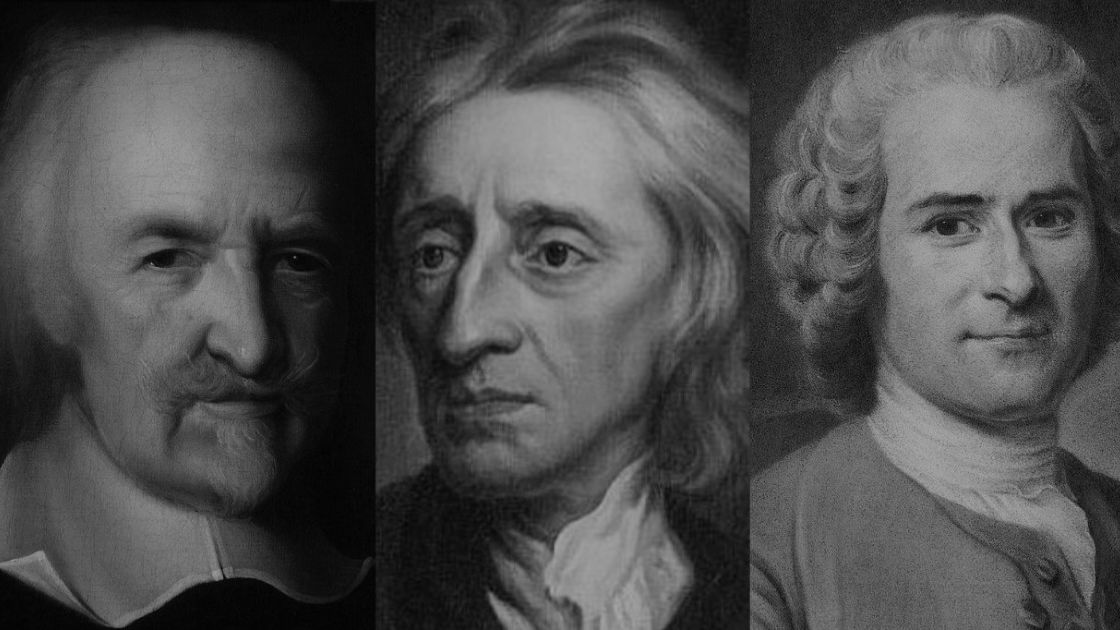

This past weekend I concluded my series on the paradox of politics, which I began in October of this year. Among the many political theorists we surveyed were Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacque Rousseau, all of whom are deservedly famous for developing a strand of political philosophy known as social contract theory. Although this influential political theory has many variants (see here, for example), a common thread is a fictional collective agreement or “social compact” in which individuals in a state of nature consent, either implicitly or explicitly, to surrender some, or even all!, of their natural liberties and freedoms to the government in exchange for protection, order, and the maintenance of property rights. Although social contract theory has played a pivotal role in modern political philosophy, does good political philosophy make for bad contract law? More specifically, what happens when we view social contract theory from a purely legal or common law lens? What, in a word, is the legal status of the social contract, and does the answer to this question depend, in turn, on whose social contract we are talking about? Would any of the fictional social contracts postulated by Hobbes, Locke, or Rousseau, for instance, be legally valid or enforceable under modern contract law doctrines, and if so, what would constitute a material breach of the social contract, and what would the proper legal remedy be? These are just some of the questions that I will explore starting tomorrow (17 December).

Monday medley: A Very Laufey Christmas

Shout out to my youngest daughter, Adys, for introducing me to Laufey’s music!

Christmas season update

I will begin a new series of blog posts in the next day or two. In the meantime, here is a compilation of my previous 12 posts on the political theories of Rousseau, Rawls, and Nozick:

- Rousseau recap

- Rousseau’s god

- Sparta or Athens?

- Rousseau’s sleight of hand

- Rawls preview

- Beware of Rousseauian wolves in Rawlsian clothing

- Beware the tyranny of Rawlsian justice

- Rawls’s empty idea of equal liberty

- Nozick’s takedown of Rawls’s difference principle

- Nozick’s slam dunk: the Wilt Chamberlain argument

- Nozick’s sandcastle

- Political philosophy as art

Political philosophy as art

“We are all libertarians …” –Dr. Julia Maskivker

Although Nozick’s valiant pincer movement against Rawls is vulnerable to counter-attack (as we saw in my previous post), Nozick is right about two things: (a) liberty matters, and (b) any attempt to achieve equality — whichever metric we use to measure equality — will come at the expense of liberty. To conclude (for now), I would only add the following additional observation: any attempt to achieve a well-ordered society (“law and order”) will also come at the expense of liberty. As a result, the $64 question is, how much liberty are we prepared to give up in order to achieve other worthy goals, such as equality, safety, or “justice”? And more broadly, is the law-liberty dilemma a “soluble” problem?

My tentative conclusion is, no it is not. Everyone (and every group) must decide for itself how much liberty he (or in the case of a group, it) is willing to trade off in exchange for equality, safety, etc., or vice versa, how much equality, safety, etc., one is willing to trade off for liberty. That is the paradox of politics in a nutshell, and as I see it, there is no scientifically “falsifiable” answer (in the Popperian sense) or single solution to this question. It’s all a matter of preferences, or perhaps aesthetics.

And on this note (aesthetics), I like to compare the great minds I have surveyed thus far — Hume and Smith, Locke and Nozick, Rousseau and Rawls — to the “Old Masters” of our Western art tradition. By way of illustration, just as many accomplished artists from different eras — Caravaggio, El Greco, and Gauguin come to mind — have painted the same pivotal moment in the life of Jesus in different ways, the famous “Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane” that took place between the Last Supper and Jesus’s arrest, so too have the great minds of political philosophy presented their own original portraits of liberty.

For Nozick, for example, liberty is the absence of coercion or interference from others, especially the state. For Rawls, it is the first of his two principles of justice: “an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.” And for Rousseau, it is obedience to the general will. Yes, we are all libertarians, but how much? Which of these competing conceptions of liberty is the “right” one? For my part, I am inclined to agree with Nozick. Rousseau’s general will is too dangerous, while Rawls is just a Rousseauian wolf in classical liberal clothing. Nozick’s nightwatchman state is not just the lesser evil; it is my aesthetic ideal.