Alternative Title: Review of Robert Sanger, “Gettier in a Court of Law” (Part 2)

Picking up where we left off in my previous post, let’s now turn to the second part of Professor Sanger’s Gettier paper, where he shows how the rules of evidence are able to untangle Gettier problems. To see this, let’s return to Professor Sanger’s hypothetical Gettier problem involving a shepherd. Specifically, imagine a scenario in which one of his sheep has trampled on a neighbor’s garden. The neighbor then sues the shepherd seeking compensation (money damages) for the destruction of his garden on the theory that the shepherd had a common law or statutory duty to “fence-in” his sheep. Call this “The Case of the Negligent Shepherd.” (This title, however, is something of a misnomer, as historically speaking the tort of trespass was a strict liability tort, but let’s set that detail to one side as my title has a nice ring to it.)

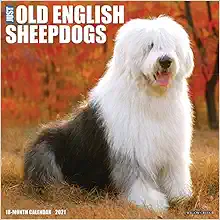

Further imagine, in keeping with Sanger’s original hypo, that the shepherd raises an affirmative defense–the sheep was in his field at the time and thus could not have trampled on the neighbor’s garden–and at trial, or more likely during his pre-trial deposition, the shepherd testifies under oath: “I saw my sheep in my field at noon on that particular day.” (Sanger, 2018, p. 416.) Then, on cross-examination, the neighbor’s lawyer introduces Exhibit A, a close-up photograph of the shepherd’s field, which was taken on the same day and time that the shepherd claims to have seen his sheep in his field and which shows a dog, like the one pictured below. (In reality, this photograph would have most likely been produced during the discovery phase of the case, leading to settlement or summary judgment, but let us ignore this pesky detail for now.) The lawyer then cross-examines the shepherd as follows: “I direct your attention to that dog. Isn’t a fact that you saw the dog and not your sheep?” (Ibid.) To avoid committing perjury, the shepherd concedes that it is a dog: “You are right. From my vantage point, the dog did look like my sheep. Now that you show me this photograph, I must admit I saw the dog and not my sheep.” (Ibid.)

Philosophically speaking, the shepherd was claiming on direct examination that he had a “justified true belief” that the sheep he thought he saw was, in fact, a sheep in the field (and thus had knowledge of the sheep being in the field), but on cross examination this claim turned out to be based on a false belief. In reality, the sheep was a dog–a breed of “sheep dog” like the one pictured above. As a result (Sanger, 2018, p. 417), the shepherd “cannot make a broader claim under the Rules of Evidence (or logic) that because he saw a dog he deduced that his sheep must be somewhere else in the field ….” Sanger’s full legal analysis appears on page 417 of his paper (footnotes omitted) and is worth quoting in full:

“Testimony can be offered as either direct evidence or circumstantial evidence. Direct evidence is offered to prove a fact, e.g., it is probative to the claim that the witness saw the sheep in the field at the relevant time. Circumstantial evidence is offered to prove circumstances that create an inference that another fact is true, e.g., the witness saw sheep hoof prints in the field as circumstantial evidence that may be probative to the claim that a sheep had been in the field. Professor Gettier’s caveat about a deduction of P from Q would be relevant to circumstantial but not to direct evidence. But here, and in all Gettier problems, the claim is of direct evidence, not circumstantial. It is not proffered that a false belief of seeing a sheep on this side of the hill would be a circumstance that could support a deduction that there was a sheep on the other side of the hill. Hence, in a court of law the false belief that he saw his sheep would not be admitted as evidence that there was a sheep somewhere else in the field.”

To the point, Sanger uses the case of the negligent shepherd to argue that a “justified true belief” cannot constitute knowledge of a fact when one’s belief turns out to be false. According to Sanger (pp. 417-418), for example, “The judge would not instruct the jury … that, ‘If you do not believe that [the shepherd] saw his sheep, and you conclude that he saw a sheep-like dog, you may consider his testimony as circumstantial evidence that a sheep was somewhere else in the field.’ To the contrary, if the jury concluded that [the shepherd] saw a dog, his testimony would have no probative value whatsoever as to whether a sheep was anywhere else in the field.”

To sum up, for Sanger (p. 420) a person’s claim to knowledge in a Gettier problem “is parallel to a claim of a witness in court who testifies to personal knowledge of a fact.” Therefore, if the witness’s belief turns out to be false, the rules of evidence would require a jury to reject the witness’s claim, even though the witness may have at one time had a “justified true belief” about his claim! I therefore take the main lessons of Sanger’s paper to be as follows. Although Gettier cases may seem to be rare or exotic occurrences, in reality Gettier cases occur all the time, especially in law cases, and the rules of evidence used by judges at trial can easily deal with these special cases without too much fuss. In other words, with the rules of evidence, we don’t need to “overthink” (my words, not Sanger’s) Gettier cases.

Sanger’s shepherd hypo, however, is highly stylized. It is highly improbable that this simple case would have ever gone to trial under our existing system of civil litigation, which is time-consuming and expensive; it is more likely that it would have been settled out of court or would have resulted in a “summary judgment,” a ruling by the judge without the need for a jury. So, I will consider a more realistic and compelling example of a Gettier case in law in my next post. I will return to the Zapruder film and talk about legendary New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (who is pictured below), the only prosecutor to bring a criminal case in connection with the assassination of JFK.

Pingback: Postscript: the problem of photographic evidence | prior probability