As I mentioned in a previous post, Toshiaki Ota’s presentation on “The roles of judges in Adam Smith’s jurisprudence” was one of my favorite works at this year’s meeting of the International Adam Smith Society (IASS). In summary, Professor Ota makes three crucial points in his draft paper:

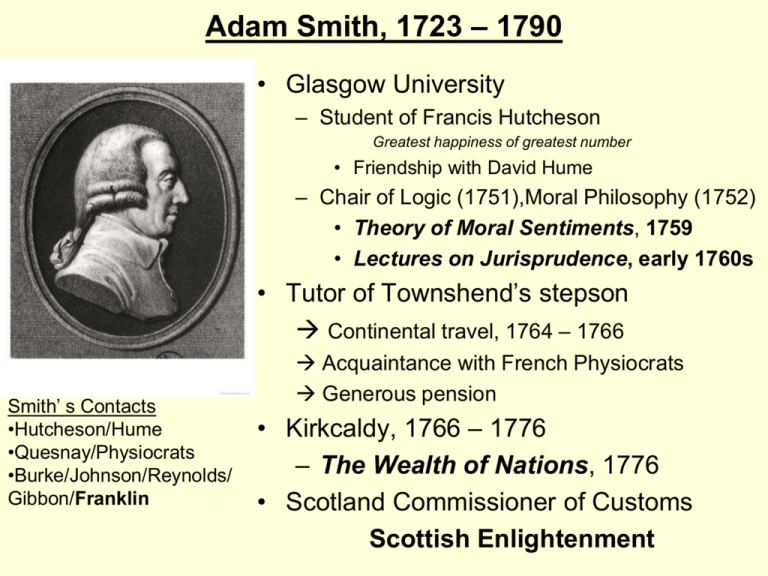

- Correspondence between Law Judges and Impartial Spectators? According to Professor Ota, some Smith scholars, such as Knud Haakonssen, see a correspondence between Smith’s “impartial spectator” in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) and Smith’s theory of law in his Lectures of Jurisprudence (LJ), especially his views on the pivotal role of judges in legal systems. (For a timeline of when Smith developed these ideas, see the slide pictured below.) What is the correspondence? On the one hand, the impartial spectator in TMS is a fictional being who judges the morality and propriety of our actions, while on the other hand, flesh-and-blood judges in legal systems are public actors who should strive toward impartiality when judging disputes and law cases.

- Ota’s Contribution. Professor Ota, however, invites us to reconsider this supposed correspondence between law judges and impartial spectators. Why? Because Smith himself had a negative view of law judges. Specifically, Smith identified two structural problems with the administration of justice that would make it difficult for law judges to maintain their impartiality: (i) judicial salaries — i.e. judges whose salaries depend on litigation fees will be tempted to favor the party paying those fees –, and (ii) the limited nature of the judicial power — i.e. judges must rely on the political branches (the king and parliament in Smith’s day; the president or prime Minister and legislature in ours) to enforce their decisions. Or in the immortal words of Alexander Hamilton in Federalist #78: judges lack the power of the sword and the power of the purse.

- Continuing Relevance of Smith’s Critique of Judges. For my part, I wish to add the following observation before concluding my review of Ota’s paper: Although the first problem (re: judicial salaries) was solved by the framers of the U.S. Constitution by granting judges lifetime tenure with a salary guarantee, the second problem (re: the limited nature of the judicial power) is built into the system government: the Congress has the power of the purse, a power over which courts have no control, and the president (executive branch) has the power of the sword: he decides which laws to enforce, and how to enforce them.

- Correspondence between the Jury and the Impartial Spectator. Lastly, Professor Ota concludes his draft paper by drawing a correspondence between jurors and impartial spectators. According to Ota, Smith thought jurors would be impartial for two reasons: (i) the parties in a case have the ability to remove a biased juror from the jury during voir dire or the jury-selection process, and (ii) jurors must reside “near the place where the crime was committed, that they may have an opportunity of being acquainted with it” (quoting Smith’s Lectures on Jurisprudence (B), p. 72).

Alas, Point #4 is where Professor Ota’s paper breaks down and needs to be further developed, for there are two massive problems with Smith’s view of the jury. First and foremost, there is no guarantee that the parties to a case will be able to eliminate all biased jurors during the jury-selection process. (Also, on the issue of bias, I can’t help but add that perhaps we should be asking a different question instead: “What is the optimal level of bias in a jury?”) Secondly, jurors who reside “near the place where the crime was committed” are likely to have some knowledge about the facts of the case ahead of time. In other words, as Ota himself notes in his draft (p. 10), the jurors are likely to be “well-informed spectators”, but isn’t there an inherent tension between the goal of impartiality and the state of being informed about a case?

Aside from my two criticisms of Ota, I still loved his work because I agree with him (and Smith) that judges and jurors must strive to be “impartial spectators” and that legal systems should be designed with this aim in mind.

This sounds like an excellent paper.

However, I still believe that point#2 has a lot of veracity. The remedies are specific to the rules set for in American law. Therefore, may not apply to all nations. It should be noted that these concerns are more salient in illiberal regimes.

Even in the United States, judges still face an incentives issue. As in any subset of the political process, all actors (including those involved in the administration of law) still face non-monetary benefits. The guarantee of tenure and salary eliminates most perverse incentives faced by politicians. This does not prevent/eliminate personal interests from obscuring impartiality.

good points; also, what is remarkable is the breadth and range of Smith’s ideas!