Alternative title: Who is Adam Smith’s impartial spectator?

Adam Smith’s “impartial spectator” is an idea that has fascinated me for as long as I can remember–see here, for example. In summary, Smith’s spectator metaphor goes back to his moral-philosophical treatise The Theory of Moral Sentiments, where Smith first invented the idea of an impartial observer or imagined third party who makes it possible for an individual to objectively judge the ethical status of his or her actions. But who exactly—or what—is this imaginary entity?

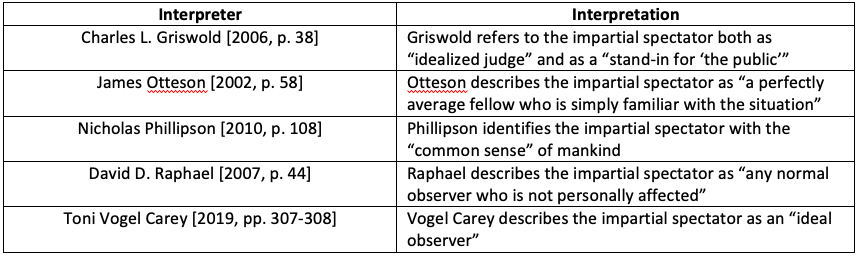

In a paper published in Volume 11 of The Adam Smith Review, independent scholar Toni Vogel Carey (see her impressive research bio here) offers a new and intriguing interpretation of Smith’s impartial spectator. To the point: she compares Smith’s spectator to the “ideal observer” in scientific thought-experiments. For Vogel Carey, that is, Smith’s moral spectator is supposed to be a close approximation of an unbiased or perfectly impartial observer with perfect information, and in support of her interpretation of the impartial spectator, Vogel Carey cites four Smith scholars: Charles L. Griswold (author of Adam Smith and the Virtues of Enlightenment), James Otteson (Adam Smith’s Marketplace of Ideas), Nicholas Phillipson (Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life), and David D. Raphael (The Impartial Spectator: Adam Smith’s Moral Philosophy). Alas, these Smith scholars describe the impartial spectator in radically different ways.

Nicholas Phillipson, for example, identifies the impartial spectator with the “common sense” of mankind, while David D. Raphael describes Smith’s spectator as “any normal observer who is not personally affected.” Both of these interpretations of the impartial spectator, however, pose two further questions: how ideal–or close to ideal–is the common sense of the public, and where does one draw the “not personally affected” line? Likewise, James Otteson describes Smith’s spectator as “a perfectly average fellow who is simply familiar with the situation,” and by the same token, Charles Griswold refers to Smith’s spectator as a “stand-in for ‘the public’.” But, again, how ideal–or close to ideal–is an “average fellow” or “stand-in for ‘the public’,” and how much “familiar[ity] with the situation” is required?

Worse yet, by my count there are at least three different interpretations of Smith’s spectator: 1. the impartial spectator as an ideal observer (Vogel Carey’s interpretation); 2. the spectator as a hypothetical average fellow or stand-in for the public in the aggregate (Otteson; Griswold); and last but not least, 3. the spectator as any ordinary or “normal” individual observer with “common sense” (Raphael; Phillipson). So, which of these interpretations is best, and what criteria should we use for deciding which particular interpretation is best? Those questions no doubt merit their own paper; in the meantime, however, I am posting below my “impartial spectator scorecard”:

Also, for the record, below the fold is a bibliography of the works I have cited in this blog post:

- Griswold, Charles L. 2006. Imagination: moral, science, and arts, in Knud Haakonssen, editor, The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith, pp. 22-56. Cambridge University Press.

- Otteson, James R. 2002. Adam Smith’s Marketplace of Ideas. Cambridge University Press.

- Phillipson, Nicholas. 2010. Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life. Yale University Press.

- Raphael, David D. 2007. The Impartial Spectator: Adam Smith’s Moral Philosophy. Clarendon Press.

- Vogel Carey, Toni. 2019. Adam Smith’s Newtonian ideals. Adam Smith Review, Vol. 11 (2019), pp. 297-314.

Pingback: Hume, Smith, and probabilistic truth | prior probability