Alternate title: Why Coase is the GOAT (part 3 of 3)

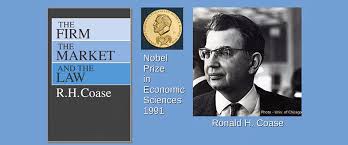

Hyper-blogger Tyler Cowen has nominated six men as the greatest economists of all time (GOAT) in his excellent new work on the history of economics: Milton Friedman, John Maynard Keynes, F. A. Hayek, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Malthus (really?), and Adam Smith. Put aside the fact that Lord Keynes is way overrated (see here, for example). As I mentioned in a previous post, the economist with the strongest claim to GOAT status (after Adam Smith) appears in passing only twice in Professor Cowen’s new work: Ronald H. Coase. I already explained why Coase is the GOAT in this post. Here, I will address (and respond to) a different question: why the Hell did Cowen snub Coase?

For Cowen, to be even considered for GOAT status an economist must not only have had original ideas with great historical import; he must also “have a hand in both macro and micro”. Alas, macro is Coase’s achilles heel, for his two most famous works — “The Problem of Social Cost” (1960) and “The Nature of the Firm” (1937) — focus mostly on such micro questions as the problem of harmful effects, i.e. so-called negative externalities, and the logic of industrial organization, i.e. why do we have firms? Coase has thus little or next to nothing to say about macro issues or the economy as a whole. So, how can Ronald Coase be the GOAT when his contributions to macroeconomics are nil? There are at least three reasons why:

- The “Revisionist Ronald Coase” argument. First off, one could argue that Coase did, in fact, make meaningful contributions to macro. To begin with, Coase’s critique of welfare economics (or what Coase himself calls the “Pigovian tradition”) poses a direct challenge to standard macro models. In brief, Coase claimed that the fundamental distinction between “private cost” and “social cost” in welfare economics was pure nonsense because harms are reciprocal in nature, not uni-directional. When a factory pollutes the air, for example, should the factory owner be paid to shut down, or should the downwind neighbors be paid to move to another location? The distinction between private and social costs is totally and utterly irrelevant to these questions!

- The “big question in macro” argument. The other contribution Coase made to macro, though perhaps an indirect one, was his overall comparative and agnostic approach toward what I call “the big question” in econ: when to rely on decentralized markets and when to make room for centralized command-and-control. Unlike Coase’s pragmatic and agnostic approach, all macroeconomists share the same fatal flaw: their macro models presume that command-and-control methods of manipulating the economy will have their desired effect, i.e. that macro-scale economic interventions will work out the way they are supposed to. Coase, however, called bullshit. In his seminal social cost paper, Coase himself extolled his fellow economists “to take into account the costs involved in operating the various social arrangements (whether it be the working of a market or of a government department), as well as the costs involved in moving to a new system. In devising and choosing between social arrangements we should have regard for the total effect. This, above all, is the change in approach which I am advocating.” Just because Coase’s approach toward the big question is all but ignored by most academic economists doesn’t mean Coase is wrong, which leads me to my third and final point for now …

- The “dog that didn’t bark” argument. Whether or not you accept my revisionist take of Coase’s work, one could still argue, in the alternative, that Coase’s overall silence towards macro itself constitutes a statement: a condemnation of what has truly become a bullshit and faddish field. Writing in 2016, for example, no less an economic authority than Paul Romer wrote: “The methods and conclusions of macroeconomics have deteriorated to the point that much of the work in this area no longer qualifies as scientific research. The treatment of identification in macroeconomic models is no more credible than in the first generation large Keynesian models, and is worse because it is far more opaque. On simple questions of fact, such as whether the Fed can influence the real fed funds rate, the answers verge on the absurd.” (Romer’s devastating critique of macroeconomics is available here.) Romer is not the only economist to diss macro, but he is, perhaps, the second-most prominent one to do so (after Coase, that is).

Pingback: Sunday assorted links - Marginal REVOLUTION

Pingback: Sunday assorted links | Factuel News | News that is Facts

Pingback: Sunday assorted hyperlinks - Marginal REVOLUTION - The Owl Report

I have never liked Keynes. His worked has frequently been distorted to justify the old consensus on profligate spending policies.

The new wave of MMT makes insight look fiscally conservative. MMT is still in its nascent stage of existence.

Malthus shouldn’t even be on Cowen’s list, the one concept he is best known for turned out to be wrong. He had a point about scarcity and the possibility of consumption never meeting an equilibrium, but he didn’t anticipate technological advancement fixing this problem. There are some extremely narrow situations where his insights might apply (in the context of an extremely abstract appication)but should be applied sparingly.

F.A. Hayek and Smith are deserving of being on the list. I am not fully sold on Rothbard and Mark Blaugh’s accusations of Smith being a plagiarist.

But yes, Coase unquestionable deserve a spot on Cowen’s list

agree, but I have to say, Cowen’s book is really fun to read!

It makes sense its a good read. He’s basically the older version of Bryan Caplan.

An academic economist who writes about free-market economics in serious tone, but is entertaining and accessible to intelligent laypeople.

nailed it!!!

I should also add, they both write about a number of areas of interest outside of economics as well.

But ideologically, they both depart a little bit..

Caplan = AnCap

Cowen= States-capacity libertarian/ minarchist

Pingback: Sunday assorted links - AlltopCash.com

I don’t find this argument persuasive. His argument about externalities is still microeconomics. It doesn’t tell us about money, inflation, the business cycle, the unemployment rate or growth.

Yes, I concede you are correct about Coase’s argument; but my larger point is this: what if macro is just bullshit, as Paul Romer suggests? If so, then I don’t hold Coase’s lack of macro bona fides against him!!!

There’s a lot of BS within macro, but I wouldn’t say the whole thing is BS. The connection between printing money & inflation is solid. Scott Sumner’s writing (mostly building on Lucas & Friedman) holds up.

That’s the business cycle, which is notoriously politicized, and for that reason Romer criticized the development side of macro. And there is indeed a lot economists don’t know about development. But Romer was complaining that economists were writing mathematically impossible models, and that argument of impossibility can be disproved by counterexample:

https://andolfatto.blogspot.com/2015/06/competitive-innovation.html

excellent observations!

PS: thanks for your comment, and for taking the time to read my post!