I hate to be “that guy” — especially among my fellow libertarian friends — but the more I study the law and economics of tariffs in U.S. history, the more I realize that my colleague and co-author (see here) Salim Rashid is most likely right about the limited influence of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations on economic policy during his (Smith’s) own lifetime (see here, for example), and the more I can begin to comprehend the popular appeal of President Trump’s pro-tariff policies. For a good overview of the history of tariffs in the United States, see here. Alas (spoiler alert), tariffs and protectionist policies at the national level were the norm, not the exception, when our republic was founded.

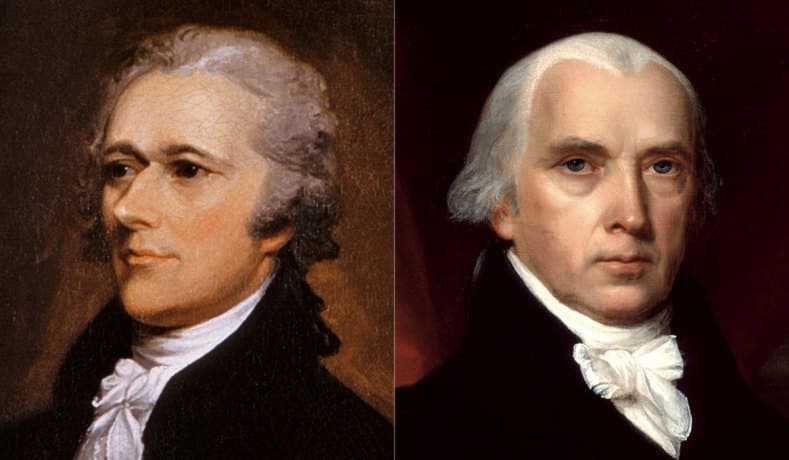

Two cases in point are James Madison’s Tariff Act of 1789 — the first major law passed by the first Congress! — and Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures. (The full text of Hamilton’s report is available here. ) Although Hamilton’s proposals for government bounties to promote domestic industries failed to receive support from Congress, virtually every tariff recommendation put forward in the report was adopted in the five-page Tariff Act of 1792. (See here.) That said, any intellectually-honest person has to agree that Adam Smith’s general argument against trade barriers is still spot on. The “problem” for us free traders, however, is that Smith himself made several pragmatic exceptions to his general free-trade rule. I will explore whether Trump’s new round of tariffs, including his 10% across-the-board tax on imports from all nations, falls into any of Smith’s exceptions in a future post.

It’s interesting to look at historical precedents

indeed! 💯

The one question I have is why are economic fallacies so enduring ?

I feel like we never truly stopped arguing against the mercantilism of Smith’s day.

In isolation , the short term effects of many economically flawed policies sound good.

Once the reality hits (case in point the current tariff panic) , people tend to have buyer’s remorse.

I will tell you why: because most people have still not read Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations !!

I have … but I think most people regardless of what they have read are still susceptible to economic policies because flashy rhetoric is more appealing than facts.

I have acted in the Hayekian sense as a “second hand dealer of ideas” and most people laugh me off. Especially , the MAGA crowd, most of their economic precepts are grounded in the right-wing variant of “feel good policies”. I never thought I’d see the day right-wingers would adopt their own version of the quixotic and whimsical thinking ( which is typically a characteristic of the left-wing ethos). But this new and poisonous strain of conservatism is completely divorced from pragmatism.

** still susceptible to flawed economic policies **