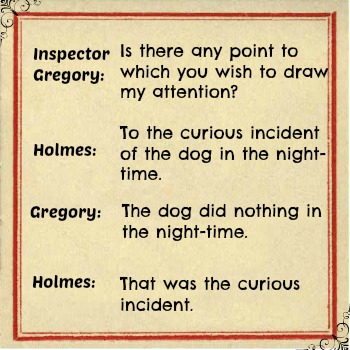

As I mentioned previously (see here and here), both the Department of Defense and the Space Force recently published new policies spelling out their current commercial outer space strategies. In summary, both of these jargon-laden reports identify a wide variety of critical “priority missions” or “mission areas” that the U.S. military must meet in outer space and envision a greater partnership between the U.S. military and the commercial space sector, calling for our national security agencies to buy the services and systems they need for their outer space operations from private commercial providers instead of building these systems themselves. But there is something missing from these new policies. Like the dog in the Sherlock Holmes story that did not bark, both reports share a big blind spot: they don’t discuss the “tragedy of the outer space commons”, i.e. the problem of space congestion and space junk.

Let’s begin with the Pentagon’s new space report “Commercial Integration Space Strategy” (released on April 2, 2024), which begins by describing the need for “a safe, secure, stable, and sustainable space domain” (p. 1, para. 1). Despite this promising introduction, the DoD’s “Commercial Integration Space Strategy” fails to mention how our growing demand for commercial space services will most likely continue to produce a proliferation of satellite constellations and other spacecraft in an already congested Low Earth Orbit (LEO). Likewise, although the Space Force’s 2024 “Commercial Space Strategy” (dated April 8 2024) refers to outer space as an “increasingly congested and contested domain” (p. 1), it too contains absolutely no discussion of how to achieve “sustainability” in outer space, or of the risks of greater spacecraft congestion and space junk — zero, nada, zilch!

Both reports, however, do take a step in the right direction by carving out a larger role for markets — and for the free enterprise system more generally — in U.S. outer space policy, i.e. the decision whether to buy or build. In addition, both reports explicitly identify “responsible conduct” as one the four foundational principles of U.S. outer space policy. At a minimum, doesn’t this general reference to “responsible conduct” include some regard for the problems of space congestion and space debris? As it happens, building on my previous work (see here), my colleague and friend Justin Evans and I have decided to research the possibility of defining property rights in outer space, a proposal that we will be writing up as a joint addendum to the DoD’s “Commercial Integration Space Strategy” and the Space Force’s “Commercial Space Strategy”. Simply put, we propose solving the tragedy of the outer space commons by expanding the use of markets to include well-defined property rights in orbits and the ability for those rights to be traded. I will further discuss our proposal in the next day or two …

Pingback: Digression: RAND Report on Commercial Space Services | prior probability

Pingback: Lit review: survey of proposed solutions to the tragedy of the outer space commons | prior probability