Adam Smith’s last days in Paris were marked by a terrible tragedy: the death of one of the pupils under his care, Hew Campbell Scott (pictured below), who was only 19 years old at the time. Below is an excerpt from Chapter 8 (“Grand Tour Questions”) of my forthcoming survey of open Adam Smith problems with Salim Rashid (footnotes are below the fold):

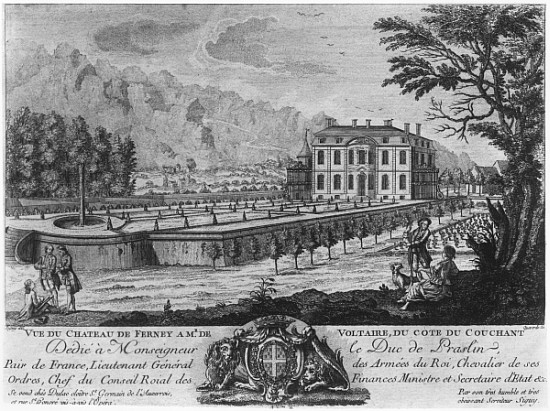

“What was the fatal ‘fever’ that Adam Smith’s pupil Hew Campbell Scott contracted in Paris in the fall of 1766, and how did he contract this disease? Initially, John Rae (1965/1895, p. 226) had reported that Hew had been murdered on the streets of Paris: ‘[Smith’s] younger pupil, the Hon. Hew Campbell Scott, was assassinated in the streets of Paris, on the 18th of October 1766, in his nineteenth year.’[1] But two pieces of personal correspondence, both of which are written in Smith’s hand only four days apart (15 & 19 October 1766; Corr. Nos. 97 & 98), were subsequently discovered. In summary, the first of these letters reports that Hew had contracted a fever; the second letter tells us that Hew’s fever was a fatal one. Interestingly, both of Smith’s missives are addressed to Lady Frances, the sister of Hew and Duke Henry.[2] Also, of all of Smith’s extant letters postmarked in France, his 15 October letter to Lady Frances is the longest: a total of 894 words. (The second-longest piece of correspondence Smith wrote during his travels in France, a letter addressed to Charles Townshend, contains 626 words. See Corr. No. 95.)

“By his own account, Smith wrote his 15 October letter late at night—11 o’clock P.M.—and it contains many gruesome details of Hew’s illness. Among other things, Smith reports on Hew’s many ‘vomitings’, ‘purgings [that] continued with great violence’, and ‘delirium’, and he also describes how Hew had ‘bled very copiously at the nose’ (Corr. No. 97). By comparison, Smith’s next letter to Lady Frances, dated 19 October 1766 (Corr. No. 98), is laconic and to the point:

It is my misfortune to be under the necessity of acquainting you of the most terrible calamity that has befallen us. Mr Scott dyed this Evening at seven o’clock. I had gone to the Duke of Richmonds in order to acquaint the Duke of Buccleugh that all hope was over and that his Brother could not outlive tomorrow morning: I returned in less than half an hour to do the last duty to my best friend. He had expired about five minutes before I could get back and I had not the satisfaction of closing his eyes with my own hands. I have no force to continue this letter; The Duke, tho’ in very great affliction, is otherwise in perfect health. I ever am etc. etc. (Corr. No. 98)

“Alas, although Hew had received the best medical care he could have possibly received in the Enlightened Paris of his day and age, his illness was a fatal one. For his part, Smith had consulted with three eminent doctors in all—François Quesnay, who had previously attended to Hew’s older brother, Duke Henry; Richard Gem, the doctor assigned to the British embassy in Paris (see Armbruster 2019, p. 131); and Théodore Tronchin (see Corr. No. 97)—but according to E. H. Campbell and Andrew S. Skinner (1982, p. 135), ‘The doctors had little idea of what was wrong or what to do.’ Furthermore, according to Ian Simpson Ross (2010, p. 231), it was Hew’s untimely demise that cut short Smith’s travels in Europe: ‘In all likelihood Smith would have stayed in France until 1767, the year of the majority of the Duke of Buccleuch’ had it not been for ‘a dramatic change of plans occasioned by the fatal illness of the Hon. Campbell Scott in October 1766.’[3] But upon Hew’s untimely demise, Smith’s grand tour would come to an abrupt end.

“This final chapter of Smith’s grand tour travels thus poses many unanswered questions. Why, for example, did Smith address his letters announcing Hew’s illness and death to Hew’s young sister, Lady Frances, and not to his mother, Lady Dalkeith, or stepfather, Lord Townshend? Also, in his correspondence with Lady Frances, Smith had initially described Hew’s condition as a “fever”, but what was the true cause of his death?”

Continue reading →